Vida Rabbani : Pakhshan Azizi, my cellmate, has been sentenced to death.

Vida Rabbani’s Heartfelt Plea from Evin Prison for Cellmates Facing Execution

July 31, 2024

Vida Rabbani, a journalist, human rights activist, and prisoner, has written a poignant letter from Evin Prison, where she shares a cell with Narges Mohammadi, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate of 2023. The letter comes in response to the shocking news of Pakhshan Azizi and Sharifeh Mohammadi’s execution sentences, which has left everyone in Evin Prison in a state of distress.

“We are more citizens when in courts than ever”

Vida Rabbani : “Sometimes we are citizens with rights , and therefore, as rational beings with willpower, legal authority can be exercised over us, and we can become subjects of political order. Other times, as the Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben describes, we are “homo sacer,” meaning bare life or mere existence—biological, animalistic life devoid of any rights or status.

In those moments when batons come down repeatedly, when bullets tear through flesh, or when an eye is shattered, when we are trampled underfoot… what are we in those moments? Are we humans with rights, and dignity, or are we just pieces of skin, flesh, and bone abandoned?

But in courts, however, we are always citizens who must be accountable.

In exceptional conditions that constantly transform into norms and rules, in the confrontation of bodies, when facing an authoritative officer, we are reduced to mere life, to nothing. Our rights are easily suspended, we become targets of violence, and again, this rightless body is crammed back into the shell of a citizen because court appearances are reserved for citizens.

A rightless and irresponsible entity cannot be taken to court.

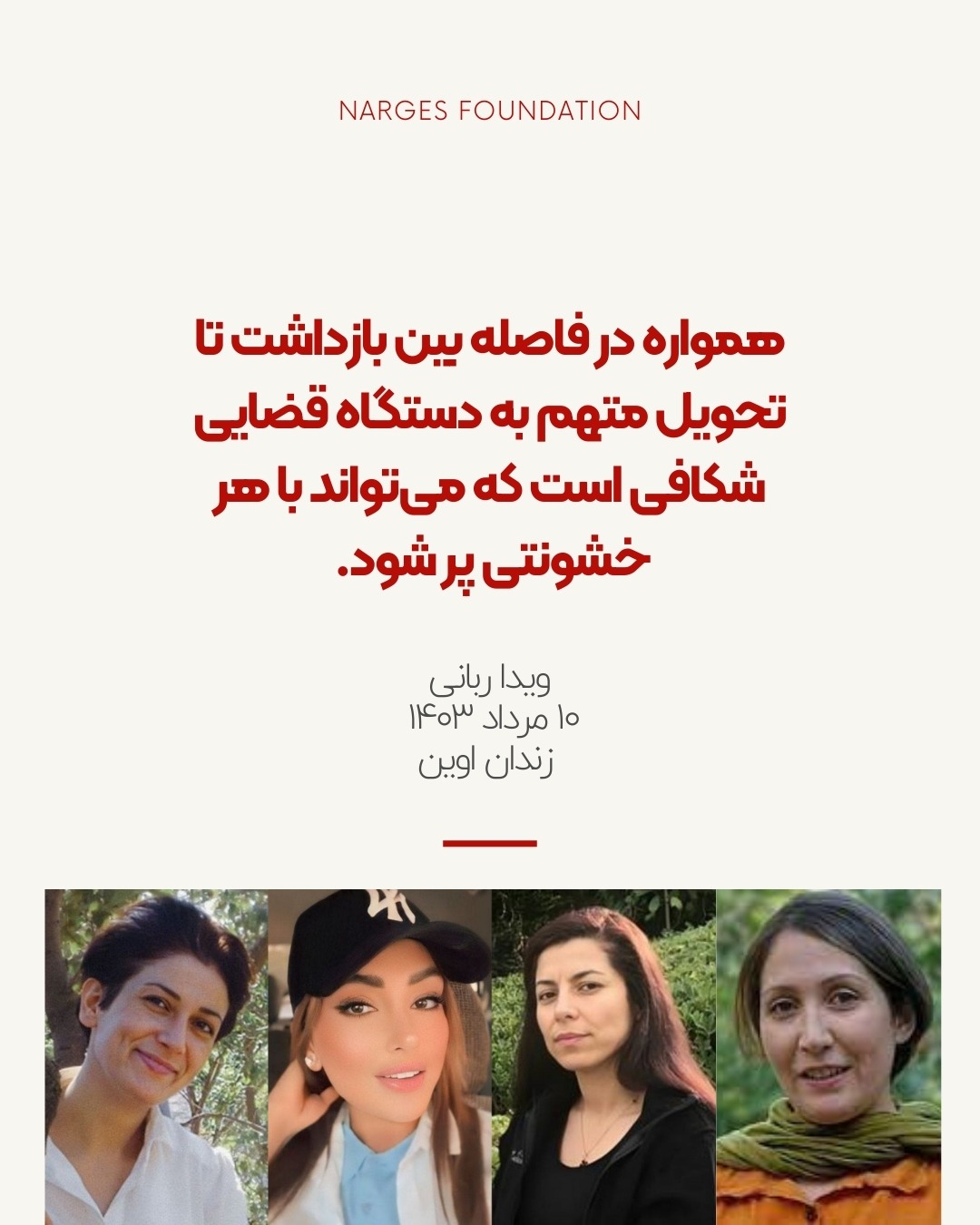

Pakhshan Azizi, my cellmate, has been sentenced to death, while two other cellmates, Nasim Simiyari and Vishe Moradi, are also facing the threat of execution.

They have become citizens, and thus the law must be applied to them. Pakhshan, during that “state of exception” I mentioned—a state that has turned into a norm and rule—was subjected to torture and abuse for several months, according to her own account in a letter she released. When Pakhshan’s head was slammed against the wall, she was mere life, and the law did not defend her. However, today that same legal authority recognizes her as a citizen deserving of execution.

In ancient Rome, “homo sacer” was a legal term for individuals who could be killed without the killer being regarded as a murderer. This concept essentially carried two meanings: both sacred and cursed. Cursed because the law did not defend them, and sacred because they could only hope for divine protection.

Nasim Simiyari lives this dual state. She spent several months in a Revolutionary Guards’ safe house, in a state of nowhere and unprotectedness, stripped of legal rights. Like the cursed human not protected by law, and the sacred human whose only protector could be God. We spent long hours with Nasim in the prison yard, talking about each of our arrests and interrogations. Nasim would sometimes make small references to what she endured in those months. Amidst laughter and scattered conversations, I heard that Nasim, under pressure to confess, would faint from the pain and weakness.

Nasim, in those few months of detention, had no rights; she was mere life, a life without dignity and human rights.

A gap that is filled with violence.

There is always a gap between the arrest and the handover of the accused to the judiciary system, a gap filled with various forms of violence. In this gap, individuals are stripped of their rights, becoming defenseless against the violence perpetrated by authorities.

I want to address this gap—the period between arrest and transfer to judicial custody—which is the most perilous and defenseless moment for detainees. What supervision exists during this time? What rights does the detainee have, and if any rights are violated, how can they prove it?

Even if we consider Nika Shahkarami’s story as media fabrication, is such a tragedy truly impossible? No! There is no oversight of officers from the time of arrest to handover to a legal authority, and I have experienced this firsthand.

Isn’t it true that usual protocols are set aside in special conditions?

Today, it seems we are entering a new state of exception. The same rightless women, the same mere life, now become citizens so they can be taken to court and given the heaviest possible sentence—death.

It seems we are more citizens in courts than ever before.”

July 31th, 2024

Evin Prison Iran – Vida Rabbani

ما در دادگاهها بیش از هر زمان شهروندیم

ما گاه شهروندان دارای حق و مسئولیت هستیم و بنابراین به عنوان موجودی دارای عقل و اراده میتوان بر او اقتدار قانونی اعمال کرد و سوژه امر سیاسی قرار داد و گاه به تعبیر جورجیو آگامبن، فیلسوف ایتالیایی، ما “هوموساکر” یعنی حیات برهنه یا حیات صرف هستیم، حیات بیولوژیک حیوانی که هنوز دارای هیچ حق و منزلتی نیست.

در آن لحظاتی که باتون ها با ضربات پیاپی فرود می آیند، گلوله ها پوست تن را میشکافد یا از فاصله ای نزدیک حباب چشمی را می ترکانند، در آن لحظه ای که زیر پوتین لگدمال میشويم و… در آن لحظات چه هستیم؟ بشر دارای حق و مسئولیت و شان انسانی یا تکه ای پوست و گوشت و استخوان رها شده؟ در دادگاه ها ولی ما همواره شهروندانی هستیم که باید پاسخگوی اعمال خود باشیم.

در شرایط استثنایی که مدام خود را به نرم و قاعده بدل میکند، در رویارویی بدن ها، در تقابل با آن مامور دارای اقتدار ما به حیات صرف و به هیچ بدل میشویم. حقوق ما به سادگی به تعلیق در میآيد، آماج خشونت میشويم و دوباره آن تن بی حق شده در کالبد شهروندی چپانده میشود، برای اینکه حضور در دادگاه مختص شهروندان است، چرا که پرنده ای بی حق و مسئولیت را نمیتوان به دادگاه برد.

پخشان عزیزی، همبندی من، حکم اعدام گرفته است و دو همبندی دیگرم نسیم سیمیاری و وریشه مرادی در خطر حکم اعدام هستند. آنها شهروند شده اند و باید قانون بر آنها اعمال شود. پخشان در همان “وضعیت استثنایی” که به آن اشاره کردم، آن وضعیتی که خود را به نرم و قاعده تبدیل کرده برای چند ماه به روایت خودش در نامه ای که از او منتشر شده، مورد شکنجه وآزار قرار گرفته است. وقتی سر پخشان به دیوار کوبیده میشد، پخشان حیات صرف بود و قانون از او دفاع نمیکرد، اما همان اقتدار قانونی امروز او را به عنوان شهروند شناسایی و مستحق اعدام میداند.

در روم باستان هومو ساکرها در اصطلاح حقوقی افرادی بودند که میشد آنها را کشت بدون اینکه قاتل شناخته شد. این مفهوم در واقع واجد دو معنای انسان مقدس و هم لعنت شده است، لعنت شده است چون قانون از او دفاع نمیکند و مقدس است زیرا تنها میتوانستند به حمایت خدایان امید داشته باشند.

نسیم سیمیاری همین وضعیت دوگانه را زندگی میکند. او چندماه را در خانه امن سپاه گذرانده در ناکجایی و در بی پناهی، در رها شدگی از حقوق قانونی. مانند همان انسان لعنت شده ای که قانونی از او حمایت نمیکند و همان انسان مقدسی که تنها حافظ جان او خداست. ما ساعت های طولانی را با نسیم در هواخوری زندان گذرانده ایم و هر یک از بازداشت ها و بازجویی هایمان حرف زده ایم. نسیم گاهی تنها اشاره های کوچکی به آنچه در آن چند ماه بر سرش آورده اند، میکرد. من لا به لای خنده ها و حرف های پراکنده شنیدم که نسیم زیر فشار برای اعتراف از شدت درد و ضعف از هوش میرفته است.

نسیم آن چند ماهی که در بازداشت بود هیچ حقی نداشت، نسیم در آن چندماه حیات صرف بود، حیات بدون شان و منزلت و حقوق انسانی.

فاصلهای که میتواند با خشونت پر شود

همواره در فاصله بین بازداشت تا تحویل متهم به دستگاه قضایی شکافی است که میتواند با هر خشونتی پر شود. در این فاصله دیگر بشری دارای حقوق وجود ندارد، حقوقش به تعلیق در میآید و در برابر خشونتی که ساخته اقتدار قانونی است، بی دفاع شود.

میخواهم از این فاصله بگویم از فاصله بین بازداشت تا تحویل به مرجع یا مرکزی قانونی که پر مخاطره ترین و بی پناه ترین لحظات بازداشتی ها است. در این بازه زمانی چه نظارتی وجود دارد؟ بازداشتی چه حقی دارد و اگر حقی از او گرفته شد چگونه باید آن را اثبات کند؟

حتی اگر داستان نیکا را ساخته و پرداخته رسانه ها بدانیم، چنین فاجعه ای غیر ممکن است؟ نه! نظارتی بر ضابط ها در هنگام بازداشت تا تحویل به مرکزی قانونی وجود ندارد و من این را بی واسطه تجربه کردهام.

مگر جز آن است که در شرایط ویژه پروتکلهای معمول کنار گذاشته میشود.

امروز هم گویا به شرایط استثنایی جدیدی وارد میشویم. همان زن های بی حق شده، همان حیات صرف، حالا شهروند میشوند تا بتوان آنها را به دادگاه برد و برای او سنگین ترین حکم ممکن یعنی مرگ را صادر کرد.

گویی ما در دادگاهها بیش از هر زمان دیگری شهروند هستیم.

۱۰ مرداد ۱۴۰۳

زندان اوین – ویدا ربانی