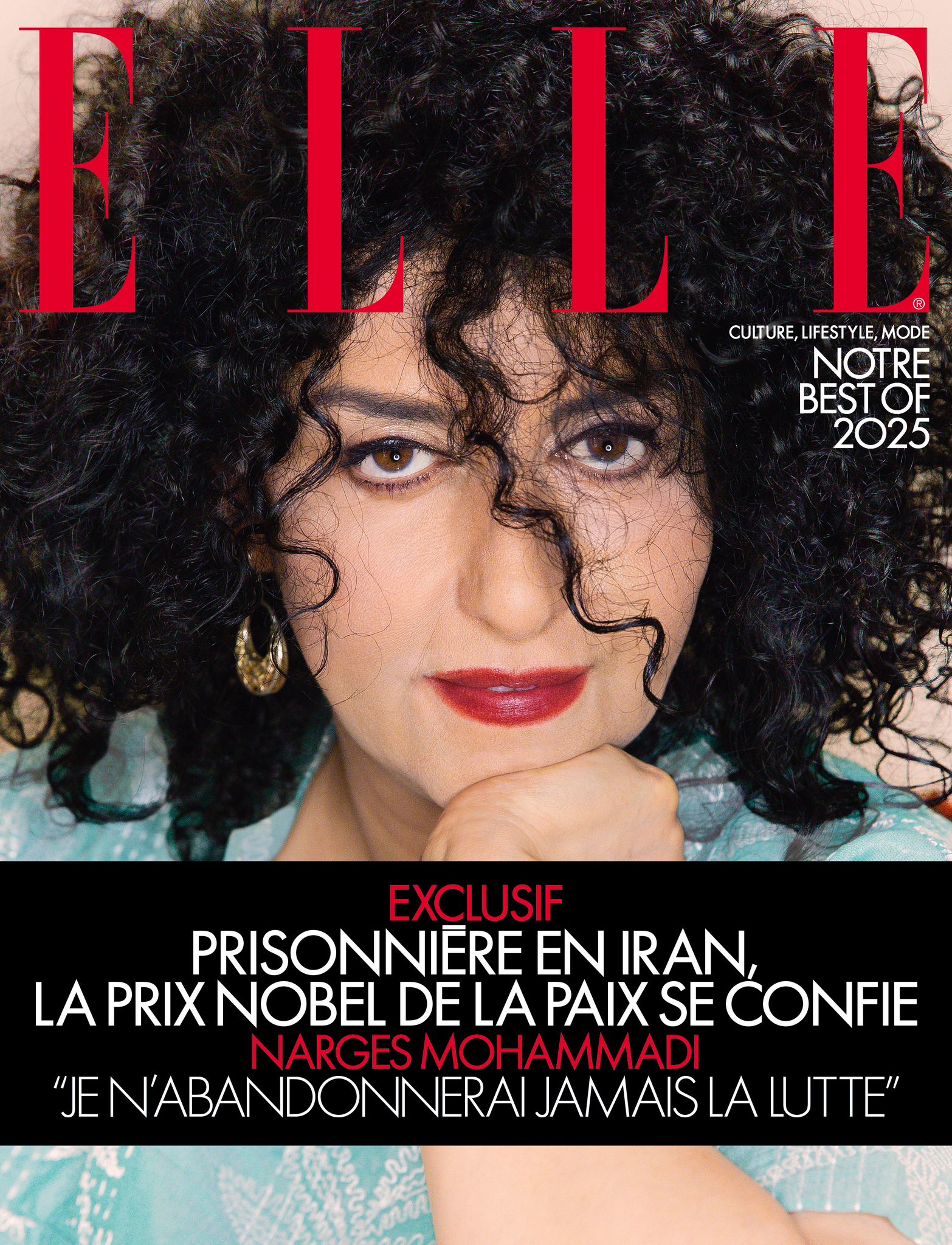

Narges Mohammadi Discusses Iranian Women’s Fight for Rights in an Exclusive Interview with Elle

NARGES MOHAMMADI Interview with Elle France for – January 2025 – Tehran

“OUR TORTURERS WILL NOT BREAK US”

ELLE: You were able to leave prison temporarily, How are you feeling?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: Physically, I have become weaker after undergoing surgery. Over the past years, continuous arrests, solitary confinement, denial of leave, and repeated opposition to receiving medical care have severely impacted my physical health. However, my spirit remains strong. Radiographs, which were finally conducted after significant delays, revealed a suspicious mass in my breast and right leg. The delay in diagnosis necessitated emergency surgery. The surgeon deemed an immediate return to prison incompatible with my health condition and recommended three months of medical leave and recovery outside prison.

Despite the surgeon’s recommendation, the authorities returned me to prison 48 hours after this major surgery, even though I could neither walk nor sit. Under these circumstances, I endured 22 days without access to medical care. In the women’s political prisoner ward, I was deprived of basic medical equipment like sterile and waterproof dressings, which were crucial for my recovery. During this challenging period, accompanied by severe physical pain, I also developed bedsores.

Thanks to the solidarity and relentless efforts of my fellow inmates—especially Vida Rabani, a journalist, and Motahareh Gonaei, a dentist—who went on hunger strike for 16 days to demand my treatment, the authorities finally relented and allowed me a 21-day suspension of my sentence for medical leave. Despite doctors’ insistence and my deteriorating health, the forensics department under the judiciary of the Islamic Republic approved only one month of leave, which was arbitrarily reduced to 21 days without any explanation.

This is neither an act of mercy nor a sign of leniency; it was a vital necessity. Moreover, this is not a suspension of my sentence or medical leave: in fact, I am required to endure the days spent outside prison under the suspension of my sentence once I return to prison.

ELLE: When you finally found yourself alone, what was the first thing you did?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: It took several hours, perhaps even a full day, to find a moment to myself—and even then, not entirely alone. In the past few days, I’ve been in constant conversation with old friends, comrades, and many human rights activists, members of civil society, feminists, lawyers, artists, intellectuals, and kind-hearted people who came to visit me. These meetings have given me strength and courage to continue our shared struggle.

One must remember that as a political prisoner, except for the time spent in solitary confinement—a narrow cell without sunlight or natural light, with no human contact except interrogators or prison guards, enduring months of sensory deprivation and complete dehumanization, a cruel form of psychological and physical torture that I addressed in my book and documentary White Torture—you are rarely alone in the general ward.

During these few days of leave, I’ve hardly had a moment entirely to myself. Yet, seeing all these beloved faces was deeply heartwarming. These visits have reinvigorated me to continue the struggle I share with my compatriots for equality, democracy, and resistance against the misogynistic and despotic theocratic regime of the Islamic Republic.

At night, after these visits, when I finally had brief moments of solitude, I took the opportunity to call Ali and Kiana. Sometimes, I would do the same during the day. After years of painful separation and being denied the chance to hear their voices, these moments of connection, just for us, were profoundly meaningful.

ELLE: What are your conditions of detention?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: First, I must explain that prisons and detention centers for political and ideological individuals are inherently abnormal places. These are unquestionably hostile environments dominated by various forms of state violence—physical, verbal, psychological, and symbolic. Moreover, these places detain innocent people arbitrarily, without committing any crime other than fulfilling their human duty to demand justice, equality, democracy, or women’s rights.

Solitary confinement is one of the most common tools of torture, used to break the spirit and psyche of prisoners. It is a place where political prisoners face various forms of violence, even death. I have personally documented severe torture and sexual violence against my fellow inmates. Despite this, as political prisoners, it is crucial for us to fight for life and the continuation of true living. This steadfast resolve of political prisoners against the officers and policies of the regime demonstrates that the government cannot succeed in breaking us. Life must always triumph, even in the face of violence and death imposed on us.

This tireless effort, even in conditions where life in prison seems anything but normal, is in itself a form of resistance against the political regime. It is a daily struggle in prison, where we strive to sustain life, build a small community, and assert human rights through the efforts of political prisoners. Ultimately, the political prisoner emerges victorious. For instance, through hundreds of hunger strikes, relentless protests, and refusing to surrender, we have collectively achieved significant victories.

In the women’s ward of Evin Prison, we engage in various activities. We allocate time for study, gatherings, and discussions about women’s issues, exchange ideas, hold political and intellectual debates, exercise, organize plays and performances, undertake collective activities to strengthen social bonds, sing songs, and even celebrate with joy and dancing.

In prison, staying spirited and active is vital because, for a political prisoner, morale is the key to enduring deprivation, separation from loved ones, and violence. Recently, 45 out of 70 women prisoners gathered in the prison yard to protest and stage a sit-in against the execution sentences of two fellow inmates, Pakhshan Azizi and Verisheh Moradi. Despite severe opposition from prison authorities, we often hold protest sit-ins in the prison yard, chanting against execution sentences, gender apartheid, and the oppressive policies of the Islamic Republic.

In response to these actions, the authorities punish us by restricting visitation rights, cutting off phone access, and imposing additional sentences through the Revolutionary Courts, whose legitimacy I do not recognize.

The women’s section of Evin Prison is a place where the violence of the authoritarian, misogynistic, and religiously oppressive regime persists. However, it is also a place where women resist, asserting life and vitality in defiance of these conditions.

ELLE: What have you endured during your years of detention?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: In 2021, I was held in solitary confinement for 64 days without interrogation, denied phone access for 40 days, and had no visits throughout the 64 days. Following this, I was taken to court for trial wearing slippers, a chador, and a blindfold, without the presence of a lawyer or access to my case file. I refused to defend myself in this court, whose legitimacy I do not recognize, and was sentenced to eight years and three months in prison and 74 lashes.

Subsequently, I was transferred to Qarchak Prison, south of the capital, a place with horrific conditions. Later, I was moved to Evin Prison in Tehran, where I remain. For more than two years, I have been denied the right to speak with my children. Since receiving the Nobel Prize in October 2023, my phone access has been completely cut off, even with relatives in Iran.

I have been deprived of my right to meet with a lawyer and have frequently been subjected to visitation bans with my family. Every statement I make carries the risk of new charges, and I am consistently faced with new accusations and convictions. This is a heavy price to pay for freedom, but it is also a duty.

ELLE: Who are your fellow cellmates in the women’s ward of Evin prison?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: In the women’s ward of Evin Prison, we are over 70 political & ideological prisoners, representing all walks of life, all ages, and various political orientations. Some of my cellmates, even after enduring long periods of imprisonment, receive new heavy sentences. Here, you will find journalists, writers, intellectuals, individuals from different faiths, including Baha’is & Kurds, women’s rights activists, &… My cellmates are strong, inspiring women.

ELLE: Upon your 21 day temporary leave on December 4, 2024 you did not wear a forced hijab and chanted “Woman, life, freedom.” What did you feel at that moment?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: When the ambulance door opened, I had conflicting emotions. I didn’t feel good about leaving my fellow inmates behind, knowing they weren’t with me, and a part of me still felt left behind in prison. But when I saw the bustling streets of Tehran after so many years, with some women walking freely without mandatory hijabs, their hair uncovered, I felt a momentary sense of joy and freedom.

For a brief moment, I experienced a minimal sense of being free when I noticed there were no security guards around me, and I was alone, walking the streets without escorts. The atmosphere of the street also reminded me that “Woman, Life, Freedom” is still alive. Deep in my heart and soul, I yearn for the day when true freedom is achieved—a day when we can witness the end of oppression and religious tyranny together.

ELLE: This movement began two years ago. From prison, how did you see it evolving?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: I believe it is the strength of this movement that has made the Islamic Republic hesitate to enforce the Hijab and Chastity Bill passed by the Islamic Consultative Assembly. Not only has “Woman, Life, Freedom” not faded away, but it has also infiltrated various aspects of people’s lives in new forms, as Iranian women and men continue to find creative ways to keep it alive.

ELLE: On November 2, 2024 Ahou Daryaei, a 30-year-old student, undressed in front of Azad University in Tehran and walked the street in her underwear. What did her gesture inspire in you?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: Her protest against what we call coercion resonated globally. Women in Iran, like women elsewhere in the world, are using various forms of protest to challenge the violation of their rights, seriously questioning those who trample upon their freedoms.

ELLE: In your opinion, is this a movement against the Islamic Republic Regime or for women’s rights? How would you define it?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: The Islamic Republic regime views the subjugation of women—half of society—as a strategic cornerstone for consolidating its power and tyranny, as well as maintaining control not only over women but over the entire society. By imposing mandatory hijab, they control women’s bodies and place them under their dominance, a form of subjugation that extends systematically to the whole society. Women, by targeting this regime’s oppressive domination, demand their rights and resist suppression. If we succeed in dismantling this domination, we will contribute to the collapse of tyranny.

ELLE: What has your Nobel Peace Prize changed?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: I believe it is our duty as human rights defenders to be the voice of the Iranian people in their struggle for freedom, equality, and democracy. It is perhaps our responsibility, as Nobel laureates worldwide, and particularly in the Middle East, to be the voice of oppressed women in these countries. I think our most important mission is to have gender apartheid criminalized at the United Nations. These regimes and governments that ignore women’s rights, subordinate them, make their lives unbearable, endanger them, or coerce them to maintain power must be fought. Criminalizing gender apartheid is one way to achieve this. I have asked for it in writing in a letter addressed to António Guterres, the Secretary-General of the United Nations.

ELLE. In 2023, you declared: “Do you hear the faint sound of the wall of fear cracking? Soon, we will hear it collapse.” In your opinion, what will happen in Iran this year?

NARGES MOHAMMADI:This momentum of the people toward democracy, freedom, and equality is unstoppable. It is based on a long tradition of struggles by Iranians and stems from a growing awareness. Victory is inevitable, but the road ahead will not be without trials.

ELLE. You haven’t seen your two children for years and are very rarely in contact with them. Were you able to speak with them after your release from prison?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: In the first hours following my release, I spoke with Ali and Kiana. They have changed so much that I could hardly believe it. When I heard their voices and saw them on video call, I realized how much they had grown—not only in size but also in maturity. All my loved ones had told me how proud they were when they spoke confidently on my behalf at the Nobel Prize ceremony, but I hadn’t personally witnessed their impressive development. I haven’t seen them in nearly ten years. I feel guilty because part of me thinks that my struggle has stolen their innocence, their youth, and forced them to grow up despite themselves. The Islamic Republic steals fragments of our lives and separates families. I hope they can forgive me for all this and understand my fight for freedom.

ELLE. They are 18 years old and are old enough to understand your struggle. Do you still sometimes refrain from telling them everything or invent stories to protect them?

NARGES MOHAMMADI:Ali and Kiana witnessed the repeated arrests of their father and me from the age of three. I believe they were exposed to the harsh realities of Iran earlier than they should have been. They have lived through and experienced these realities. I try to seize every opportunity, like this temporary release from prison, to speak with them.

ELLE. What do you think about before falling asleep at night?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: About Ali and Kiana. Often.

ELLE. Do you ever dream of beautiful things at night?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: Very often. I have such pleasant dreams that in the morning, I wake up with a deep sense of joy as I open my eyes in the room I share with thirteen other cellmates.

ELLE. You finished writing a book in prison. Are you still writing it today?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: Yes. I finished my autobiography, and I plan to publish it very soon. I am writing another book about the assaults and sexual harassment committed against female detainees in Iran. I hope it will be published soon.

ELLE. You were offered freedom on the condition that you leave the country. You refused and are paying a high price for it. Is compromise incompatible with the struggle?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: The regime has repeatedly offered me freedom on the condition that I abandon my activism, but I have always refused because freedom is non-negotiable. Any compromise would be a betrayal of my values. When my children were still young, the security services tried to make me stop fighting against the death penalty and collaborating with Shirin Ebadi, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate. They promised I could establish an NGO, but I firmly rejected their offer and was sentenced again for my activities. Once more, before my children were forced to leave the country for their safety, the regime suggested I leave the country secretly. Despite all the love I have for my children, I have always said that my place is in Iran, to fight against the regime.

ELLE. Despite your terrible daily life in prison, do you sometimes manage to feel happy?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: Yes. Every time I feel the resistance alive within me, I experience hope and joy. We live through resistance.

ELLE. Why did you take the risk of doing an interview?

NARGES MOHAMMADI: I believe it is our duty as human rights activists to amplify the struggle of the Iranian people, ensuring it resonates with audiences worldwide. We must call on the international community to support Iran’s fight for democracy, freedom, and equality, and to stand as the voice of the Iranian people, ensuring they are not abandoned on this challenging path. For this mission, I am prepared to take any necessary risk.

January 2025 – Elle Magazine France

گفتگو نرگس محمدی با مجله ال فرانسه – ژانویه ۲۰۲۵

“شکنجهگران ما نمیتوانند ما را بشکنند”

سوال: شما توانستید موقتا از زندان خارج شوید. حال شما چطور است؟

نرگس محمدی:

به لحاظ جسمی بعد از عمل جراحی ضعیف شده ام. طی سال های اخیر بازداشت های مداوم ، سلول های انفرادی ، محرومیت از مرخصی و مخالفت های مکرر از دریافت مراقبتهای پزشکی به شدت بر سلامت جسمی من تاثیر گذاشته است، اما روحیه ام بسیار عالی است.رادیوگرافیهایی که با تأخیر بسیار بالاخره انجام شد، حضور یک توده مشکوک در سینه و در پای راست من را نشان داد. تاخیر در تشخیص باعث شد که نیاز به جراحی اورژانسی پیدا کنم. جراح بازگشت فوری به زندان را ناسازگار با وضعیت سلامتی من دانست و سه ماه مرخصی پزشکی و بهبودی خارج از زندان را درخواست کرد.اما برخلاف توصیه پزشک جراح، مقامات پس از ۴۸ ساعت بعد از این عمل جراحی سنگین مرا دوباره به زندان بازگرداندند، حتی در حالی که نمیتوانستم راه بروم یا بنشینم.

در این شرایط بازگشت به زندان به همراه ۲۲ روز محرومیت از دسترسی به مراقبتهای پزشکی سپری شد. من در بند زنان زندانی سیاسی،از تجهیزات ساده پزشکی مانند پانسمانهای استریل و ضدآب محروم بودم که بسیار حیاتی بود. در این دوره سخت همراه با درد شدید جسمی، دچار زخم بستر هم شدم.

به لطف همبستگی و مبارزه بی وقفه همبندی هایم، به ویژه ویدا ربانی خبرنگار، و مطهره گونه ای دندانپزشکی که برای درخواست درمان من به مدت ۱۶ روز اعتصاب غذا کردند، حکومت سرانجام تسلیم شد و به من اجازه داد به مرخصی ۲۱ روزه توقف حکم دسترسی پیدا کنم.

با وجود تاکید پزشکان و وضعیت نامناسب سلامتی من، پس از درخواست وکیلام مصطفی نیلی، پزشک قانونی تحت نظر قوه قضائیه جمهوری اسلامی تنها یک ماه مرخصی را تایید کرد که داستان آن را بدون ارائه هیچ توضیحی به ۲۱ روز توقف حکم کاهش داد. این نه لطف است و نه نشانهای از رأفت، بلکه یک ضرورت حیاتی بود. همچنین این یک تعلیق حکم یا مرخصی درمانی نیست: در واقع من باید پس از بازگشت به زندان روزهایی را که با توقف حکم در بیرون زندان هستم را تحمل کنم.

سوال – وقتی بالاخره خود را تنها یافتید، اولین کاری که انجام دادید چه بود؟

نرگس محمدی:

چند ساعت حتی شاید یک روز کامل طول کشید تا قدری تنها باشم و حتی نه کاملاً تنها. در روزهای گذشته، من به طور مداوم با دوستان قدیمی و همرزمانم و بسیاری از فعالان حقوق بشر، اعضای جامعه مدنی، فمینیستها، وکلا، هنرمندان و روشنفکران و مردمی که با مهربانی به ملاقاتم آمدند، گفت و گو داشتم. این دیدارها به من قدرت و شجاعت دادند تا مبارزه مشترکمان را ادامه دهیم.

باید در نظر داشت که وقتی شما یک زندانی سیاسی هستید، به جز زمانی که در سلول انفرادی قرار میگیرید، یعنی سلولی باریک بدون نور خورشید و طبیعی و بدون هیچ ارتباط انسانی جز با بازجو یا زندانبانها برای ماههای طولانی همراه با تحمل محرومیت های حسی و انسانیزدایی کامل که نوع بی رحمانه ای از شکنجه روانی و جسمی است، همانطور که در کتاب و مستندم “شکنجه سفید” به آن پرداختهام. در بند عمومی به ندرت تنها هستید.

در این چند روز مرخصی واقعاً لحظهای کاملاً برای خودم نداشتم، اما دیدن تمام این چهرههای دوستداشتنی برایم بسیار خوشایند بود. این دیدارها به من برای ادامه مبارزهای که با هموطنانم برای برابری، دموکراسی و مقابله با حکومت استبدادی دینی زنستیز و مستبد جمهوری اسلامی به اشتراک گذاشتهام، نیروی تازه ای بخشید.

شب ها پس از دیدارها وقتی بالاخره برای لحظاتی کوتاه فضای خلوتی داشتم ، از فرصت استفاده کرده ام و با علی و کیانا تماس گرفته ام، همانطور که گاهی در طول روز این کار را انجام می دادم، تا پس از سالها جدایی دردناک، بدون اینکه اجازه شنیدن صدایشان را داشته باشم، لحظهای فقط برای خودمان داشته باشیم.

سوال – شرایط زندان چگونه است؟

ابتدا باید به طور کلی توضیح دهم که زندان وبازداشتگاه افراد سیاسی و عقیدتی ، ذاتا مکانی عادی نیست. این مکان قطعاً محیطی خصمانه است که در آن انواع خشونتهای حکومتی حاکم است. منظورم خشونت جسمی، کلامی، روانی و نمادین است. علاوه بر این که در این مکان، انسان های بیگناهی که به طور خودسرانه و بدون ارتکاب هیچ جرمی جز انجام وظیفه انسانی خود، مطالبه عدالت، برابری، دموکراسی یا حقوق زنان در آنجا بازداشت میشوند، حضور دارند.

انفرادی یکی از رایجترین ابزارهای شکنجه است که برای شکستن روح و روان زندانیان استفاده میشود. سلول مکانی است که در آن زندانیان سیاسی در معرض انواع خشونت و حتی مرگ قرار می گیرند . من به طور شخصی موارد شکنجه شدید و خشونت جنسی علیه هم بندانم را مستند کردهام. با این حال، برای ما به عنوان زندانیان سیاسی بسیار مهم است که برای زنده بودن و تداوم زندگی واقعی مبارزه کنیم. این سیاست و اراده محکم زندانیان سیاسی علیه ماموران و سیاستهای حکومت است که بتوانیم عملا نشان دهیم که حکومت در شکستن ما موفق نخواهند شد. زندگی همیشه باید پیروز شود، حتی در برابر خشونت و مرگی که آنها تلاش دارند بر ما تحمیل کنند.

این تلاش خستگی ناپذیر حتی در شرایطی که زندگی در مکانی چون زندان عادی به نظر نمی رسد، به خودی خود یک مقاومت در برابر رژیم سیاسی است. این یک مبارزه روزانه در زندان است، جایی که ما تلاش میکنیم تا زندگی را ادامه دهیم، جامعهای کوچک بسازیم که در آن حقوق انسانی از طریق تلاشهای زندانیان سیاسی به دست میآید و زندانی سیاسی پیروز میشود. برای مثال، به دلیل این که زندانیان سیاسی صدها اعتصاب غذا انجام دادهاند، بدون خستگی اعتراض کردهاند و تسلیم نشدهاند، ما در مجموع به پیروزیهای جمعی چشمگیری دست یافتهایم.

در بند زنان سیاسی اوین ما فعالیت های متنوعی داریم. زمان هایی را برای مطالعه، گردهمایی و بحث در مورد زنان ، تبادل نظر و برگزاری مباحث سیاسی و فکری، ورزش کردن ، برگزاری تئاتر و نمایش، فعالیتهای جمعی برای تقویت پیوندهای اجتماعی، سرود و آواز خواندن و حتی شاد و بانشاط بودن با جشن و رقصیدن داریم.

در زندان با روحیه و فعال ماندن مسئلهای حیاتی است، زیرا برای یک زندانی سیاسی، روحیه کلید تحمل محرومیت، جدایی از عزیزان و خشونت است. اخیرا ۴۵ نفر از ۷۰ زندانی زن در حیاط زندان جمع شدند تا علیه حکمهای اعدام دو تن از همبندانمان یعنی پخشان عزیزی و وریشۀ مرادی اعتراض و تحصن کنند. ما اغلب در حیاط زندان علیرغم مخالفت های شدید از سوی مقامات زندان، با شعارهایی علیه حکم اعدام، آپارتاید جنسیتی و سیاستهای سرکوبگرانه جمهوری اسلامی تحصن های اعتراضی برگزار می کنیم . در مقابل این اقدامات زندانیان، مقامات زندان نیز ما را مجازات میکنند و حقوق ملاقات را محدود میکنند، دسترسی به تلفن را قطع میکنند و احکام اضافی از طریق دادگاههای انقلاب اعمال میکنند که من مشروعیت آنها را به رسمیت نمیشناسم. بخش زنان زندان اوین جایی است که خشونت حکومت استبدادی، اقتدارگرا و زنستیز مذهبی ادامه دارد. اما در عین حال، جایی است که زنان مقاومت میکنند و در مقابله با این شرایط، زندگی و نشاط را مطرح میکنند.

سوال – چه چیزهایی را در سالهای بازداشت و زندان خود تحمل کردهاید؟

سال ۱۴۰۰ برای شصت و چهار روز در انفرادی نگه داشته شدم، بدون بازجویی، ۴۰ روز بدون دسترسی به تلفن و ۶۴ روز بدون هیچ گونه ملاقات. پس از آن، من را با دمپایی و چادر و چشمبند، بدون حضور وکیل و دسترسی به پروندهام به دادگاه برای محاکمه بردند. من از دفاع از خود در این دادگاه که مشروعیت آن را به رسمیت نمیشناسم، امتناع کردم و به هشت سال و سه ماه زندان و ۷۴ ضربه شلاق محکوم شدم. سپس به زندان قرچک، در جنوب پایتخت منتقل شدم که شرایط آن وحشتناک است. بعداً به زندان اوین در تهران منتقل شدم که هنوز در آنجا هستم. برای بیش از دو سال، اجازه صحبت با فرزندانم را نداشتهام، و از زمانی که جایزه نوبل را در اکتبر ۲۰۲۳ دریافت کردم، دسترسی به تلفن، حتی با بستگانم در ایران، قطع شده است. از حق ملاقات با وکیل محروم شدم و به کرات به ممنوعیت ملاقات به خانواده نیز محکوم شدم. هر بیانیه ای که میدهم، خطر اتهامات جدید را به همراه دارد و مرتب با اتهامات و محکومیتهای جدید روبهرو میشوم. این بهایی سنگین برای آزادی است، اما همچنین یک وظیفه است.

سوال – همبندان شما چه کسانی هستند؟

در بخش زنان زندان اوین ما بیش از هفتاد نفر زن زندانی سیاسی و عقیدتی هستیم، از تمام اقشار جامعه، تمام سنین و تمام گرایشات سیاسی. برخی از همبندانم حتی پس از گذراندن مدتهای طولانی در حبس مجدد حکمهای زندان سنگینی دریافت می کنند. در اینجا روزنامهنگاران، نویسندگان، روشنفکران، افرادی از ادیان مختلف بهاییها، کُردها، فعالان حقوق زنان و غیره حضور دارند. زنانی قوی و الهام بخش هم بندیهای من هستند.

سوال – پس از آزادی شما در چهارم دسامبر، شما حجاب اجباری نپوشیدند و شعار “زن، زندگی، آزادی” را سر دادید. در آن لحظه چه احساسی داشتید؟

وقتی درب آمبولانس باز شد، احساسات متناقضی داشتم. از این که همبندانم را پشت سر گذاشتم و آنها همراه من نیستند احساس خوبی نداشتم و بخشی از وجود من هنوز در زندان جا مانده بود. اما وقتی خیابان پرجنب و جوش تهران را بعد از سالها دیدم،بعضی از زنان بدون حجاب اجباری با موهای باز بودند، لحظهای احساس شوق و آزادی کردم.

احساس حداقلی از آزاد بودن برای لحظاتی کوتاه داشتم ، وقتی دیدم که گارد امنیتی در اطرافم نیست و خودم به تنهایی و بدون مامورها در خیابان هستم . فضای خیابان همچنین به من نشان داد که “زن، زندگی، آزادی” هنوز زنده است. در اعماق قلب و روح خود، آرزو میکنم که آزادی واقعی به دست آید. روزی که پایان ستم و استبداد دینی را در کنار هم ببینیم.

سوال – این جنبش دو سال پیش آغاز شد. آن را در حال پیشرفت میبینید؟

فکر میکنم به موجب قدرت این جنبش است که جمهوری اسلامی جرأت اجرای لایحه حجاب و عفاف، مصوب مجلس شورای اسلامی را ندارد. نه تنها “زن، زندگی، آزادی” از بین نرفته است، بلکه در ابعاد مختلف زندگی مردم به اشکال جدید نفوذ کرده است، زیرا زنان و مردان ایرانی راههای خلاقانهتری برای زنده نگهداشتن آن پیدا میکردهاند.

سوال – در دوم نوامبر، آهو دریایی، دانشجوی ۳۰ ساله، مقابل دانشگاه آزاد تهران از خشم و در اثر فشار لباس هایش را از تن کند شد و به نشانه اعتراض در خیابان در لباس زیر خود راه رفت. این حرکت او چه احساسی در شما ایجاد کرد؟

اعتراض او به آنچه که ما آن را اجبار مینامیم، در سطح جهانی طنین انداز شد. زنان در ایران همانند سایر نقاط دنیا، از اشکال مختلف اعتراض برای به چالش کشیدن نقض حقوق خود استفاده میکنند و به طور جدی کسانی را که بر حقوق آنها پا میگذارند، مورد سوال قرار میدهند.

سوال – به نظر شما، آیا این یک جنبش علیه جمهوری اسلامی است یا حرکتی برای تحقق حقوق زنان؟ چگونه آن را تعریف میکنید؟

رژیم جمهوری اسلامی به زیر سلطه درآوردن زنان، یعنی نیمی از جامعه، را به عنوان کانونی راهبردی برای تحکیم قدرت واستبداد خود و حفظ سلطه نه تنها بر زنان بلکه بر کل جامعه میبیند. با تحمیل حجاب اجباری، آنها بدن زنان را کنترل میکنند و زن را تحت سلطه می گیرند که در مجموع این سلطه ، قابل بسط به کل جامعه است. زنان با هدف قرار دادن این سلطه گری حکومت، حقوق خود را طلب کنند و با سرکوب مقابله کنند. اگر ما موفق شویم این سلطه را از بین ببریم، به ساقط شدن استبداد کمک خواهیم کرد.

سوال – جایزه نوبل شما چه تغییراتی ایجاد کرده است؟

من معتقدم که وظیفه ما به عنوان مدافعان حقوق بشر این است که صدای مردم ایران در مبارزه آنها برای «آزادی، برابری و دموکراسی» باشیم. شاید مسئولیت ما به عنوان برندگان جایزه نوبل در سراسر جهان، به ویژه در خاورمیانه، این است که صدای زنان تحت ستم باشیم. من فکر میکنم مهمترین ماموریت ما این است که آپارتاید جنسیتی را در سازمان ملل به جرم تبدیل کنیم. این رژیمها و دولتهایی که حقوق زنان را نادیده میگیرند، زنان را تحت سلطه قرار میدهند، زندگیشان را غیرقابل تحمل میکنند، آنها را در معرض خطر قرار میدهند، یا مجبورشان میکنند با سلطه پذیری عامل تثبیت استبداد شوند که باید با آنها مبارزه کرد. جرمانگاری آپارتاید جنسیتی یکی از راههای دستیابی به این هدف است. من این درخواست را در نامهای خطاب به آنتونیو گوترش، دبیرکل سازمان ملل، به صورت مکتوب مطرح کردهام.

سوال: در سال ۲۰۲۳، شما اعلام کردید: “آیا صدای ضعیف ترکیدن دیوار ترس را میشنوید؟ به زودی خواهیم شنید که این دیوار سقوط میکند.” به نظر شما در ایران امسال چه خواهد شد؟

این حرکت مردم به سوی دموکراسی، آزادی و برابری غیرقابل توقف است. این حرکت بر پایه یک سنت طولانی از مبارزات ایرانیان است و از یک آگاهی فزاینده سرچشمه میگیرد. پیروزی اجتنابناپذیر است، اما راه پیش رو بدون دشواری نخواهد بود.

سوال: شما سالهاست که دو فرزند خود را ندیدهاید و ارتباط بسیار کمی با آنها دارید. آیا بعد از آزادی از زندان توانستید با آنها صحبت کنید؟

در ساعات اول پس از آزادیام، با علی و کیانا صحبت کردم. آنها آنقدر تغییر کرده بودند که به سختی میتوانستم باور کنم. وقتی صدایشان را شنیدم و آنها را در ویدیو دیدم، متوجه شدم که چقدر بزرگ شدهاند.نه فقط از نظر قد و اندازه، بلکه از نظر بلوغ. همه عزیزانم به من گفته بودند که چقدر به آنها افتخار میکنند زمانی که با اعتماد به نفس به نمایندگی از من در مراسم جایزه نوبل سخنرانی کردند، اما من شخصاً شاهد رشد چشمگیرشان نبودم. من آنها را نزدیک به ده سال است که ندیدهام. احساس میکنم آنها به خاطر مبارزات من مجبور به این زندگی و ترک کشور و بزرگ شدن بدون مادر شده اند. جمهوری اسلامی تکههایی از زندگی ما را میدزدد و خانوادهها را از هم جدا میکند. امیدوارم آنها بتوانند مرا بابت این سختی ها و محرومیت از خانواده در کنار هم ببخشند و مبارزهام برای آزادی را درک کنند.

سوال – آنها ۱۸ ساله هستند و به اندازه کافی برای درک مبارزه شما بزرگ شدهاند. آیا هنوز گاهی اوقات از گفتن همه چیز به آنها خودداری میکنید؟

علی و کیانا شاهد دستگیریهای مکرر پدرشان و من از سه سالگی بودهاند. من معتقدم آنها زودتر از آنچه که باید، با واقعیتهای سخت ایران روبرو شدهاند. آنها این واقعیتها را زندگی و تجربه کردهاند. من سعی میکنم از هر فرصتی، مانند این آزادی موقت از زندان، برای صحبت با آنها استفاده کنم.

سوال – شبها قبل از خواب به چه چیزی فکر میکنی؟

اغلب به علی و کیانا.

سوال – آیا شبها خواب چیزهای زیبایی میبینی؟

خیلی وقتها. خوابهای بسیار خوشایندی دارم که صبحها با حس عمیقی از شادی بیدار میشوم، درحالی که چشمانم را در اتاقی که با سیزده نفر دیگر هماتاق هستم باز میکنم.

سوال – آیا موفق به نوشتن در زندان می شوید؟

بله. خاطرات خودم را تمام کردم و قصد دارم آن را منتشر کنم. در حال نوشتن کتاب دیگری هستم دربارهی اذیت و آزارهای جنسی که علیه زندانیان زن در ایران صورت گرفته است. امیدوارم به زودی منتشر شود.

سوال – به شما پیشنهاد داده شد تا همکاری کنی اما تو رد کردی و برای این موضوع بها میپردازی. آیا مصالحه با مبارزه ناسازگار است؟

رژیم بارها به شرط کنار گذاشتن مبارزاتم پیشنهاد آزادی کرده که همیشه رد کردهام چون آزادی غیر قابل معامله است. هر معامله ای، خیانت به ارزشهایم خواهد بود. وقتی فرزندانم هنوز کوچک بودند، سرویسهای امنیتی سعی کردند من از مبارزه علیه حکم اعدام و همکاری با شیرین عبادی، برنده جایزه صلح نوبل، دست بردارم. آنها وعده دادند که اجازه خواهند داد تا یک سازمان غیردولتی را تأسیس کنم و من واضحاً رد کردم و به دلیل فعالیتهایم دوباره محکوم شدم. یک بار دیگر، قبل از اینکه فرزندانم مجبور به ترک کشور برای امنیتشان شوند، رژیم پیشنهاد داد که به صورت مخفیانه کشور را ترک کنم. علیرغم تمام عشقی که به فرزندانم دارم، همیشه گفتهام که جای من در ایران است تا علیه رژیم مبارزه کنم.

سوال – با وجود زندگی روزمرهتان که بسیار سخت است، آیا گاهی موفق میشوید خوشحال شوید؟

بله. هر بار که احساس میکنم مقاومت درونم زنده است، امید و شادی را تجربه میکنم. ما از طریق مقاومت زندگی میکنیم.

سوال – چرا خطر کردید و به سوالات ما پاسخ دادید؟

باور دارم که وظیفه و مأموریت ما این است که مبارزه مردم ایران را به گوش مردم سراسر دنیا برسانیم و از آنها بخواهیم که در مبارزه برای دموکراسی، آزادی و برابری از مردم ایران حمایت کنند. اینکه این افراد صدای ایرانیها باشند و آنها را تنها نگذارند. برای این کار من آمادهام هر ریسکی را بپذیرم.