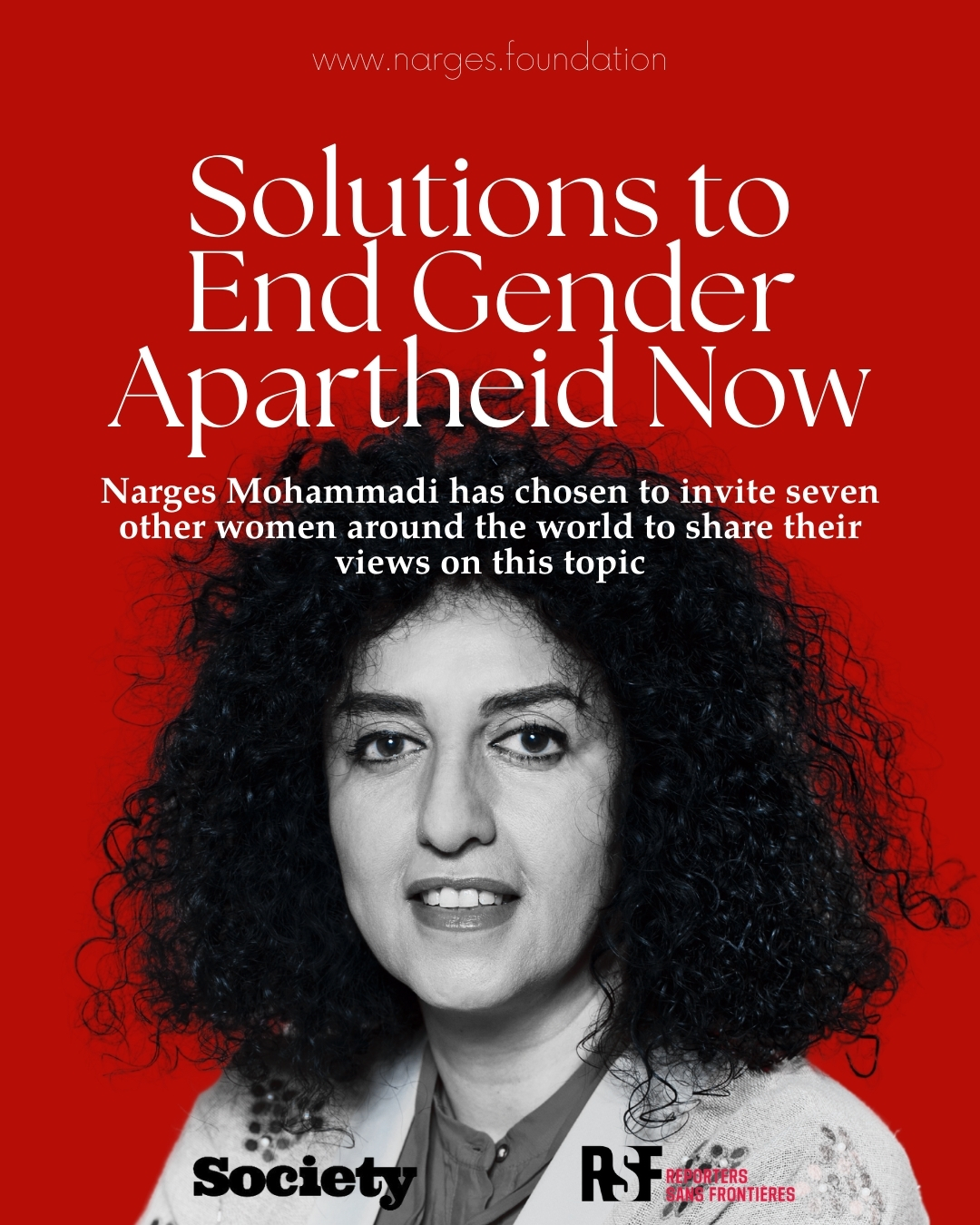

Narges Mohammadi’s Letter to Seven Influential Women: A Call to End Gender Apartheid Worldwide

HOW CAN WE END GENDER APARTHEID ONCE AND FOR ALL?

Conversations with Narges Mohammadi

Narges Mohammadi, Nobel Peace Prize laureate of 2023, has spent a total of ten years imprisoned by the Iranian regime and is currently facing another eleven years of incarceration. A prominent journalist and activist, Mohammadi is a leading voice in the fight for press freedom and women’s rights. Last March, she issued a bold call for the “criminalization of gender apartheid,” condemning the “systematic and institutionalized segregation” of women in Iran in a letter to UN Secretary-General António Guterres.

Today, from within Evin prison, Mohammadi extends an invitation to seven influential women from around the world to contribute their perspectives on this urgent issue. The dialogue aims to explore how women, united in solidarity, can effectively combat gender apartheid on a global scale. This special issue, published today, September 12, 2024, by Society Magazine and Reporters Without Borders, features a powerful conversation between Narges Mohammadi and seven distinguished voices: Shirin Ebadi, Agnès Callamard, Dr. Jane Goodall, Pinar Selek, Tatiana Mukanire Bandalire, Anne L’Huillier, and Oleksandra Matviïtchouk.

These remarkable women discuss women’s rights, the elimination of gender apartheid, and the role of sisterhood in driving change.

INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY LUCAS DUVERNET-COPPOLA, FOR NARGES MOHAMMADI. Here are their responses.

“Imagine if, in your country, the law allowed men to have four wives at the same time, but if married women had sexual relations with another man, they would be sentenced to stoning or execution. If women bore children, but men became their absolute guardians, to the point that even if they killed their children or grandchildren, they faced no repercussions due to their legal authority, yet if a mother killed her child, she would be condemned. If women worked alongside men, but their share of their father’s inheritance was half that of their brothers, and their portion of their husband’s estate was the smallest. If girls, as young as six, were required to wear the hijab just to attend school and receive an education. If married women were forbidden to leave the country for any reason, no matter how urgent, without their husband’s or father’s permission—even if they were ministers or members of parliament. If only men had the right to divorce, while women were denied this right. If the law explicitly and in every circumstance declared men as the head of the family. If women who refused to wear the hijab were barred from education, employment, social services, and even healthcare. If the law and religion proclaimed that a woman’s duty was to submit to her husband, and she had no right to refuse sex, even if he was abusive. If sexual relations between men were forbidden, with the passive partner facing execution. If sexual relations between women were banned and punished with the harshest penalties.

Under such conditions, if you protested against discrimination, oppression, inequality, and the domination of women, and were arrested, subjected to solitary confinement, white torture and a long prison sentence, what support from people around the world would soothe the pain and suffering of oppression and discrimination, making you feel that you are not alone?

As an imprisoned feminist, a women’s rights activist, and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, if you were to call on the United Nations to criminalize gender apartheid, what specific actions would you expect from feminists, human rights activists, intellectuals, and defenders of democracy and peace around the world to support this cause?”

Narges Mohammadi, Evin prison, August 2024

Shirin Ebadi Iranian political activist, lawyer, former judge, and human rights advocate, Nobel Peace Prize laureate in 2003:

“I urge women worldwide to support those who are deprived of education, whether due to political reasons like Afghan women, poverty, or other factors. The more empowered these women are, the stronger they will be in fighting discrimination.”

As the first female president of the Tehran court, what were your main challenges in breaking through the barriers of a male-dominated judicial system? How did you influence the perception of women within the judicial system in Iran?

I became a judge in Esfand 1348 (March 1970), and at that time, me being a woman was not an issue for the government. I faced no obstacles; I passed the exams like my male counterparts, succeeded, and became a judge. The Shah wanted Iran to move closer to Western civilization, so he himself initiated granting many rights to women, including the right to judge, the right to custody, and the right to divorce. Therefore, the government did not contest it, and I received support just like other women. I should also mention that I faced no problems from society. I don’t recall having specific issues because I was a woman during my tenure as a judge.

When the Iranian government excluded women from the judiciary, how did this decision affect your professional life and your work towards gender equality?

What were the immediate and long-term implications of this policy for women’s rights in Iran? After the Islamic Revolution, one of the first decisions was that women could no longer be judges. They placed me and other female judges among administrative staff. This was very disheartening, as women lost a significant part of their power. Nevertheless, it did not deter young girls or prevent them from pursuing law studies. When I was a student, our class had 200 people, with only 30 women. When my daughter graduated years later, under the Islamic Republic of Iran, there were twice as many women as men. Despite facing discriminatory conditions, women needed legal knowledge, which significantly increased their interest in law studies.

As the first Iranian woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, what challenges and opportunities did you encounter both in Iran and on the international stage? How has this achievement influenced your subsequent efforts in human rights and gender equality?

I used the Nobel Prize money to purchase an office in Iran for the NGO I co-founded and have chaired since. This office became a hub that attracted many young lawyers, including you, Narges. We provided free legal defense for political prisoners. Each month, we sent reports on human rights violations in Iran to the United Nations. We were the first to do this work, and fortunately, others have continued since. Today, several lawyers offer their services for free to political defendants and report on these cases.

What message would you send to women around the world who are striving to overcome systemic obstacles and advance gender equality?

How can they leverage their individual and collective experiences to foster positive changes in their communities and beyond? Women worldwide must recognize that the root cause of the discrimination they face is patriarchal culture. This culture exploits anything to justify itself. For instance, when religion gains power, it uses religion as a justification. We see that oppression and discrimination in Iran and Afghanistan are often justified in the name of Islam, while the true cause is patriarchal culture. In some countries, it is not the laws that are problematic but societal traditions that oppose women. Therefore, the most crucial task for women is to identify the source of discrimination. The first step is raising awareness and educating women. We understand why the Taliban have prevented women from getting an education: because they know that an educated woman will undoubtedly oppose them. I urge women worldwide to support those who are deprived of education, whether due to political reasons like Afghan women, poverty, or other factors. The more empowered these women are, the stronger they will be in fighting discrimination.

Agnès Callamard Secretary General at Amnesty International: “We have collected harrowing testimonies about how intelligence services and security forces, arrest women. They often endure hours of torture and other mistreatment, including rape or other forms of sexual violence, aimed at inflicting the greatest possible humiliation.If they can survive, speak out, and resist, how dare I not? I could never forgive myself for failing to serve justice and others.”

How can the international community better address the issue of gender apartheid, especially in countries like Iran, where women face unimaginable repression, yet the global response seems inadequate? How can this gap be bridged?

Generations of women and girls worldwide have been subjected to institutionalized and systematic violence, domination, and oppression. Countless have been killed, and many others are deprived of dignity, freedom, and equality in their daily lives. Last June, Amnesty International joined the calls of pioneering women from Iran, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, urging the international community to recognize gender apartheid as a crime under international law. This would close a significant gap in our global legal framework, give a name to a horrific form of institutionalized discrimination and oppression, and provide activists with an essential tool, regardless of where they fight. States must heed this call. This form of institutionalized oppression must be named, and it must be possible to investigate and prosecute those responsible for gender apartheid, just as it should be possible to sanction those who engage in such acts. The draft convention on crimes against humanity, a major treaty effort currently being discussed at the UN, represents a crucial opportunity to reinvigorate the fight for gender justice. The international community must seize this chance to integrate gender apartheid into international law. Simultaneously, states should use all available tools, legal or otherwise. Although gender apartheid is not yet recognized, the crimes committed can be equated with the crime against humanity of gender-based oppression. Governments should open criminal investigations in their own countries against the alleged perpetrators, under the principle of universal jurisdiction, with a view to issuing international arrest warrants. They should support the extension of the UN fact-finding mission on Iran to ensure an independent mechanism continues to collect, preserve, and analyze evidence of crimes against women and girls under international law, and other egregious human rights violations. The UN Security Council should respond to the call against the states and individuals responsible for these massive violations against women and girls. International and national organizations and activists must relentlessly advocate against the indifference that too often characterizes official responses to the oppression of women and girls.

Agnès, as a witness to the systemic violence and harassment faced by women, how do you manage the emotional and psychological impact of the stories they share with you? What drives you to continue fighting for justice, despite the harrowing episodes of violence they report?

It is absolutely devastating to witness the abuses endured by women and girls within these brutal systems of oppression. In Iran, for instance, Amnesty International has gathered information on the use of rape and other forms of sexual violence to suppress the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement. We have collected harrowing testimonies about how intelligence services and security forces, both in uniform and plain clothes, arbitrarily arrest women in the streets during or after protests, at their homes, or workplaces. They often endure hours of torture and other mistreatment, including rape or other forms of sexual violence, aimed at inflicting the greatest possible humiliation. These horrors constantly remind us of the respect we owe to victims, survivors, and activists fighting to ensure such horrors never happen again, as well as our moral obligation to help them achieve justice. If they can survive, speak out, and resist, how dare I not? I could never forgive myself for failing to serve justice and others. Bearing witness is the only response, the only responsible action. My approach also involves framing the violence they experienced: understanding its personal nature, but also its systemic nature, placing it within a legal, judicial, and regulatory context, and identifying opportunities for action and redress. What continues to motivate me is, above all, the conviction that change and justice are possible. For example, when I first began working on women’s rights, it was very difficult to convince experts, our own human rights colleagues, and, of course, states, to recognize rape as a form of torture. Today, this is widely accepted, but we had to fight hard to achieve such recognition. Now, we must fight again, this time for the recognition of gender apartheid.

Oleksandra Matviïtchouk Ukrainian lawyer and activist, leader of Center for Civil Liberties NGO, Nobel Peace Prize Laureate 2022: “Your struggle is ours; my own experience has taught me that when legal processes fail, we can always rely on people. Ordinary people have more power than they realize. Our future is uncertain, but it is not predetermined by anyone. That’s why we have the opportunity to fight for the future we want for ourselves and our children”

As a human rights advocate working in Ukraine and OSCE countries, how does gender-based violence intersect with your broader efforts to document human rights violations? What approaches or strategies do you find most effective in ensuring gender issues are addressed?

For the past ten years, we have been documenting war crimes committed in the context of the conflict initiated by Russia, including sexual violence, with many survivors being women. This violence is a continuation of the war, weaponizing women’s bodies. Through certain individuals, Russian soldiers target entire communities they occupy. Survivors experience shame, their families feel guilt, and the wider community faces fear. This complex mix of emotions weakens social bonds, allowing the Russian army to maintain tighter control over occupied regions. At the same time, I don’t want to create the false impression that women in wartime are merely victims. Our experience shows that women are at the forefront of the fight for freedom and human dignity. Women serve in the armed forces, make political decisions, document war crimes, and lead community initiatives. Courage has no gender. In my view, one of the best strategies for ensuring gender equality is for women to support other women.

How can global feminist movements better integrate and amplify the voices of women and marginalized groups directly affected by conflicts and authoritarian regimes?

We must respond to women’s rights violations in other countries. Our world is highly interconnected, and the struggle of women in Iran impacts our future. Authoritarian regimes always stifle women’s voices and seek to control their decisions. Consequently, women are assigned narrowly defined roles within the family and society. This is a cornerstone of authoritarianism, as the treatment of individuals reflects how power treats its citizens. This is why, in Norway, women and men have the same rights, in Afghanistan, women are barred from universities, and in Russia, domestic violence has been decriminalized. Personal becomes political because it is always linked to how power treats people. Thus, when we fight for women’s rights, we fight for the future of our daughters. We don’t want them to have to prove to anyone that they too are human beings.

How can we establish effective international action and solidarity to end gender apartheid worldwide? And what advice would you give to Iranian women to support them in their fight for women’s rights?

Your struggle is ours. In Ukraine, we are also in a situation where the law is ineffective and the UN cannot stop Russian atrocities. But my own experience has taught me that when legal processes fail, we can always rely on people. Ordinary people have more power than they realize. Our future is uncertain, but it is not predetermined by anyone. That’s why we have the opportunity to fight for the future we want for ourselves and our children.

Anne L’Huillier French-Swedish physicist, Nobel Prize in Physics Laureate 2023: “Women must have the same access to education as men. This is a fundamental right that transcends nationalities, ethnicities, or religions. They should have access to higher education and then to industrial or academic careers in the same way as men.”

Why do sciences still seem to be a field largely reserved for men, and what can be done to change this?

Women must have the same access to education as men. This is a fundamental right that transcends nationalities, ethnicities, or religions. They should have access to higher education and then to industrial or academic careers in the same way as men. This is crucial for ensuring the advancement of science and technology, which is vital for addressing humanity’s problems and improving our living conditions. Young women will pursue scientific and technical careers if they feel supported by society, parents, teachers, etc. My experience is that a team is much more competent and effective if it is diverse. In other words, attracting women to these careers is a significant issue for humanity.

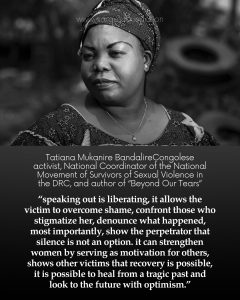

Tatiana Mukanire Bandalire Congolese activist, National Coordinator of the National Movement of Survivors of Sexual Violence in the DRC, and author of “Beyond Our Tears”: “speaking out is liberating, it allows the victim to overcome shame, confront those who stigmatize her, denounce what happened, most importantly, show the perpetrator that silence is not an option. it can strengthen women by serving as motivation for others, shows other victims that recovery is possible, it is possible to heal from a tragic past and look to the future with optimism.”

In your remarkable book Beyond Our Tears, you address, with immense courage, the torture and rape you have endured. Do you believe that sharing experiences of rape, torture, and sexual harassment can empower women? How crucial is it for them to speak openly about these experiences, both for healing and for protecting other women?

I firmly believe that sharing experiences of rape, torture, and sexual harassment can empower women by putting words to our wounds and externalizing our pain. Speaking about what we’ve endured acts as a form of personal therapy. It helps us break the silence and release the burden we carry as victims, especially when we have been forced to endure these atrocities in complete anonymity, and when society prefers to find excuses for the perpetrator and stigmatize the victim. It is not uncommon to hear people say that a victim was raped because of her clothing, for example. Being able to speak out is liberating because it allows the victim to overcome shame, confront those who stigmatize her, denounce what happened, and, most importantly, show the perpetrator that silence is not an option. Sharing these experiences can also strengthen women by serving as motivation for others. It encourages those who have always lived in silence to speak out. It shows other victims that recovery is possible, and that it is possible to heal from a tragic past and look to the future with optimism. This is precisely the mission of the National Movement of Survivors of Sexual Violence in the DRC. Through a mentoring model, we encourage survivors to support one another and move forward, knowing they are not alone and that those who have gone through similar experiences can transition from victims to leaders and agents of change in their communities.

In my country, Iran, women are arrested, imprisoned, and even killed for dancing, singing, or not wearing the hijab according to government demands. How do our cultures differ in terms of music, dance, and singing for women? And what does this reality mean to you in terms of gender apartheid?

In Iran and many other countries, women often face situations where social norms restrict their development. In some countries, women are forced to endure practices such as female genital mutilation and child marriage. Regarding music, dance, and singing, our cultures differ in that Congolese women can sing, dance, and play music without fear of arrest or risking their lives. The fact that the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is a secular state protects women because there is no law forcing them to adhere to any religious practice. The DRC also has a legal framework that protects women. For example, Article 14 of our Constitution enshrines the principle of gender parity. These legal provisions help prevent Congolese women from being arrested or killed for singing or dancing. However, the implementation of these laws remains problematic in many areas where women face various forms of abuse and violence. Often, these abuses are exacerbated by customs that impose societal codes on women. Issues such as sexual violence, child marriage, and domestic violence are still present in the DRC.

Additionally, social norms and beliefs that women are intellectually inferior to men hinder women’s progress and limit their access to education, employment, and leadership positions. During armed conflicts, sexual violence is used as a weapon of war, making Congolese women the primary victims of conflict. The sexual violence affecting hundreds of thousands of Congolese women has serious consequences on their mental and physical health, leading to their stigmatization and self-isolation. In the DRC, however, it is difficult to speak of gender apartheid because gender-based violence against women is not institutionalized. Although women face significant challenges and violence, there is no government policy aimed at discriminating against women. It is crucial to continue working to ensure that laws protecting women are effectively implemented and that customs hindering their development are fully eliminated.

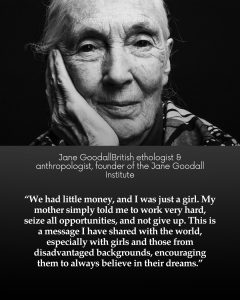

Jane Goodall British ethologist & anthropologist, founder of the Jane Goodall Institute: “We had little money, and I was just a girl. My mother simply told me to work very hard, seize all opportunities, and not give up. This is a message I have shared with the world, especially with girls and those from disadvantaged backgrounds, encouraging them to always believe in their dreams.”

Could you recount the obstacles you faced as a young woman conducting groundbreaking research on primates in Tanzania, and how you overcame them? How did your presence and work in a predominantly male field influence the scientific community and local perceptions of gender roles?

When Dr. Louis Leakey asked me if I wanted to study the behavior of wild chimpanzees —something no one had done before— I had not attended university due to financial constraints. I simply started with a love for all animals, binoculars, a notebook, a pencil, and a desire to learn more about our closest relatives. It was not really a male-dominated field. In fact, there were only three field studies in nature: gorillas in Rwanda, baboons in South Africa, and Japanese macaques in Japan. True, they were led by men, but it was primarily a new field. Being a woman even helped me: it was at a time when Tanzania was finally gaining independence from British rule, and white men were not always popular. But a young woman was, and Africans wanted to help me! It is true that when Leakey informed me he had found a place for me to pursue a PhD in ethology at Cambridge University, many media outlets claimed I received research funding merely because I was an attractive young woman (especially my legs!). However, since I was pursuing the degree only to please Leakey and wanted to return to my work with chimpanzees, I did not concern myself with what people said. In short, my situation was very different from the problems women face today.

What strategy do you consider most effective in combating systemic discrimination against women?

I have difficulty answering this question. All I can say is that I was born in 1934 into a remarkable family. We did not have much money, and it was between the two world wars. My grandmother was one of the very first women in England to get a job before marriage and taught a type of gentle gymnastics at a girls’ school. Her eldest daughter became one of the first women in England to be a physiotherapist at Guy’s Hospital. When I was 10 years old and decided that when I grew up, I would go to Africa, live with wild animals, and write books about them, everyone mocked me. How could I achieve this? We had little money, Africa was far, and I was just a girl. My mother simply told me to work very hard, seize all opportunities, and not give up. This is a message I have shared with the world, especially with girls and those from disadvantaged backgrounds, encouraging them to always believe in their dreams.

You have supported Iranian environmental activists imprisoned for their work. What inspired this commitment, and how does it reflect your broader approach to global issues related to the environment and human rights? What links do you see between systemic gender inequality and environmental degradation, and what role can women play in resolving these intertwined crises?

I was very upset that these environmental defenders—including two women—had been imprisoned for espionage. This was because they were using camera traps to record videos of shy cheetahs, leopards, etc. I included a letter of appeal for clemency, which obviously changed nothing. I then wrote to them in prison because I wanted them to know they were not forgotten. They told me it was important for their morale, so I continued. They are all free today, and that is a good thing. At the Jane Goodall Institute, we do a lot to improve girls’ education in poor regions of Tanzania and other African countries. We provide microloans to village women to start their own environmentally friendly businesses. Over my long life, I have seen many changes in attitudes toward women, although, as you know, this is not the case in countries like Iran, Afghanistan, and many others. Elsewhere, more women are reaching top political positions. There are many more female CEOs, in the armed forces, and in other fields. There are also very good forest ranger organizations. But it is also true that in many countries, women face discrimination, particularly in terms of salaries.

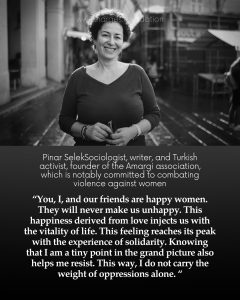

Pinar Selek Sociologist, writer, and Turkish activist, founder of the Amargi association, which is notably committed to combating violence against women: “You, I, and our friends are happy women. They will never make us unhappy. This happiness derived from love injects us with the vitality of life. This feeling reaches its peak with the experience of solidarity. Knowing that I am a tiny point in the grand picture also helps me resist. This way, I do not carry the weight of oppressions alone. “

In your work on marginalized individuals, the concept of marginality often seems to focus on specific groups. Do you believe women should be considered a marginalized group? How do the dynamics of women’s marginalization compare to those of other groups you study?

You speak appropriately of marginalized individuals rather than outsiders, which is very important. Otherwise, we might think of bizarre, antisocial, abnormal, monstrous, and troubling individuals. But, as you clearly highlight, marginality does not refer to an inherent state or characteristic of the victims of marginalization; rather, it is an act of oppression. It is not a role taken on by the victims, but rather the effects of power, which can manifest in multiple forms and degrees. Human civilization is shaped by power dynamics, and thus by struggles between submission and emancipation. To make resistance impossible or ineffective, those in power implement mechanisms of weakening, impoverishing, and invisibilizing. Marginalization is the result of this process. That is why I have never worked on marginalized groups per se, but on the mechanisms and strategies of power, for example, the links between the social construction of male bodies and the structural production of male power and political violence. I also work on collective action, that is, on social struggles in which I participate. Through my work and struggles, I have learned that the process of marginalization is not irreversible. On the one hand, oppressors aim to render their victims powerless, voiceless, impactless, and weightless; on the other hand, the oppressed mobilize their resources to overturn this strategy. For instance, we, as women, have been fighting for centuries against male powers that feed on other power dynamics. Despite this long struggle, we have not yet transformed the social order. On the contrary, it is currently reinforced by the globalization of the neoliberal economy, which revitalizes conservatisms, fascisms, and sexist powers. The growing disparities on a global scale increasingly render vulnerable those social groups at the bottom of the social hierarchy. But our struggles are also becoming stronger. As they fail to subdue us, their oppression intensifies, and we push further. This is your case, Narges. They do everything to marginalize and destroy you. And you, confined and repressed, remain uncontrollable.

In the face of persecution and hostility from your own country, how do you find the strength to continue believing in your ideals and fighting for justice? What internal resources or external support do you mobilize to stay engaged despite these adversities?

I believe that, like you, I mobilize multiple resources to find more strength. I do it constantly! My greatest resource is love, the ability to keep loving. If merely thinking about someone brings you respect and delight, you are never unhappy. You, I, and our friends are happy women. They will never make us unhappy. This happiness derived from love injects us with the vitality of life. This feeling reaches its peak with the experience of solidarity. Knowing that I am a tiny point in the grand picture also helps me resist. This way, I do not carry the weight of oppressions alone. This knowledge also gives me responsibility. I tell myself, ‘There are connections between us, little points. And if I fall, I will imbalance the other…’ Philosophical and political analyses surround me, like fireflies. I think of Gramsci’s famous observation: ‘We must combine the pessimism of the intellect with the optimism of the will.’ I see joy in the struggle against savagery. I strengthen myself by embracing pessimism. I am now stronger than in adolescence. I have learned that the world cannot change in two days. Failures, missteps, and restarts no longer overwhelm me. I do not sit idly wondering why some things do not change. I take my share of love and embraces. I also think of our friend bell hooks, who said that when feminist theories are renewed through conversations with other social critics, they can become a magic wand for changing things. Current feminist struggles explore a wide range of possibilities, with new convergences in multifaceted mobilizations. The interaction of different feminisms, different spaces, and experiences leads to the multiplication of groups, strategies, alliances, and debates. We have more tools, more experiences, and more avenues for reflection and struggle.

What does the concept of sisterhood represent for you, and when did you first experience this sense of female solidarity? How has sisterhood influenced your work and commitment to women’s rights?

My first experience of sisterhood was with Seyda, my little sister. Through her, I learned love and how to cultivate it. And through this experience, I more easily entered the field of friendship without boundaries. We grew up in the fire. We did everything to feel like we were in a fairy tale, but the author of our tale seemed to constantly test us. I remember the night of the 1980 military coup. Soldiers arrived at the house. Our father was imprisoned. Our mother fell ill. Hospital. Prison. School. Tears. Clashes. We were too small, but we held on. Hand in hand, we escaped so many fires, pulling each other out of the flames. And not once. Not a hundred times. We went through tough times. We resisted together. We learned to encourage each other. I believe that the power of experiencing immense love pushes boundaries. At least, that’s how I experienced it. As we grew up, our differences became more visible. We took different paths. We quickly understood that there was no point in being alike if we preferred a garden to a cornfield. And when I was imprisoned, Seyda left her job to study law and become my lawyer. She succeeded. For over 26 years, she has been the eyes, hands, and feet of my case. She carries the weight of my trial on her shoulders. She thinks much more than I do about what should or should not be done. With her, I learned to cultivate a love that does not rely on resemblance but arises from sharing and plurality. One experience leads to another: by learning with her to surpass myself, I opened to other sisterhoods. It was easy, it was difficult. Very difficult. Because it is hard to focus on another person, on a shorter period, with less experience. Seyda and I come from the same class, the same social background, the same conditions. To create a strong bond with other women facing different social and political difficulties requires more thought, more listening, more questioning, more discussion, and deconstruction. Effort. Always effort. Now, I see that there are many doors. Whatever they may be, when you manage to open one, you will more easily open others. I have learned to love that.

•INTERVIEWS COLLECTED BY LDC FOR NM – 12 September 2024

حقوق زنان

خواهرانگی

پایان آپارتاید جنسیتی

نامه نرگس محمدی به هفت زن تأثیرگذار جهان؛ دعوتی برای یافتن راهحلهایی جهت پایان دادن به آپارتاید جنسیتی در جهان.

در تاریخ ۱۲ سپتامبر ۲۰۲۴، با همکاری مجله سوسایتی و خبرنگاران بدون مرز، شمارهای ویژه منتشر شد که به زندانیان سیاسی در سراسر جهان اختصاص دارد. در این شماره ویژه، خبرنگاران زندانی از جمله نرگس محمدی، به مسائلی که برایشان اهمیت دارد پرداختهاند. مجله سوسایتی در توضیح این شماره نوشته است: “از آنجایی که این زندانیان قادر به انجام مصاحبهها نیستند، ما تلاش کردیم بهجای آنها از افراد موردنظرشان سوالات را بپرسیم.”

نرگس محمدی، فعال حقوق بشر برنده جایزه صلح نوبل ۲۰۲۳، موضوع آپارتاید جنسیتی را انتخاب کرده و از هفت زن تأثیرگذار سوالاتی حول محور پایان دادن به آپارتاید جنسیتی و نابرابریهای سیستماتیک علیه زنان در سراسر جهان پرسیده است.

مجله سوسایتی در ادامه توضیح میدهد: ” بخشی از این شماره ویژه، شامل نامهنگاری بین نرگس محمدی و هفت چهره جهانی—شیرین عبادی، آنگس کلامارد، دکتر جین گودال، پینار سِلِک، تاتیانا موکانیر بندالیر، آن لوئییه و اولکساندرا ماتویچوک—است و به مسئله آپارتاید جنسیتی میپردازد. هدف از تهیه این شماره ویژه، این است که به زندانیانی مثل نرگس محمدی این امکان داده شود که اگر خارج از زندان بودند و میتوانستند روی موضوعی کار کنند، آن موضوع چه میبود و ما آن را برایشان به انجام رساندیم. ما با سختی بسیار موفق شدیم نامهی سوالات را از نرگس محمدی دریافت کنیم و بهجای او از این زنان بپرسیم. نرگس بر ضرورت همبستگی زنان در سراسر جهان برای محافظت از حقوق زنان تأکید میکند و از این زنان قوی میخواهد که برای پایان دادن به آپارتاید جنسیتی—همین حالا—با هم همکاری کنند. نرگس محمدی بارها با شجاعت خواستار «جرمانگاری آپارتاید جنسیتی» شده و «تبعیض وستم سیستماتیک و نهادینه شده» علیه زنان در ایران و أفغانستان را محکوم کرده است. او بر این باور است که دری که به روی آزادی وحقوق زنان بسته است، هرگز به روی دموکراسی و برابری و آزادی گشوده نخواهد شد.”

مقدمه ، نرگس محمدی

-اگر در کشور شما قوانین به مردان اجازه دهد همزمان چهار زن داشته باشند، اما اگر زنانِ متأهل با مردی رابطهی جنسی داشتند، محکوم به سنگسار ـ یا اعدام ـ شوند.

ـ اگر زنان میزاییدند و مردان، سرپرست و ولیِ کودکانشان میشدند که حتی در صورت کشتن فرزند یا نوههایشان به موجبِ ولایتِ بر آنها مستوجب قصاص نمیشدند، اما در صورتِ ارتکابِ قتل فرزند توسط مادر، مادر مستحق به قصاص بود.

ـ اگر زنان دوشادوش مردان کار میکردند و سهمشان از ارث پدرانشان نصف برادرانشان و سهمشان از ارث شوهرانشان، کمترین بود.

ـ اگر دختران از ۶ سالگی، حتی برای ورود به مدرسه و یادگیری علم ملزم به حجاب اجباری میشدند.

ـ اگر زنان متأهل بدون اجازهی شوهرانشان نمیتوانستند کشورشان را برای هر کاری با هر میزان اهمیتی ـ حتی اگر وزیر یا نماینده مجلسِ یک کشور بودند ـ ترک کنند.

ـ اگر فقط مردان حق طلاق داشتند و زنان از آن محروم بودند.

ـ اگر قانون صراحتاً و تحت هر شرایطی مرد را رئیس خانواده میدانست.

ـ اگر زنان بدون رعایت حجاب اجباری از تحصیل، شغل، امکانات اجتماعی حتی حق درمان محروم میشدند.

ـ اگر قانون و شرع وظیفهی زن را تمکین از شوهر اعلام میکرد و زن حقِ ردِ رابطهی جنسی با هر میزان از خشونت از سوی شوهرش را نداشت.

ـ اگر رابطهی جنسی مرد با مرد لواط و حرام و مستوجبِ اعدامِ مفعول بود.

ـ اگر رابطهی جنسی زن با زن حرام و مستوجب مجازات بود.

همینطور در چنین شرایطی اگر شما به تبعیض، ستم، نابرابری و سلطه بر زن اعتراض میکردید و بازداشت، متحمل سلول انفرادی و شکنجهی سفید و تحمل حبسهای طولانی مدت میشدید، چه همراهی از سوی سایر انسانهای جهان درد و رنج ستم و تبعیض را التیام میبخشید و احساس میکردید که تنها نیستید؟

اگر بهعنوان یک فمنیستِ زندانی و برندهی جابزه صلح نوبل از سازمان ملل تقاضا میکردید با جرمانگاری آپارتاید جنسیتی که میلیونها زن هر روز با جلوهای کریه از آن مبارزه و زندگی میکنند، به فریاد زنان سرزمینتان برسند، از فمنیستها، فعالان حقوق بشر، روشنفکران و دموکراسیخواهان و صلحطلبان جهان انتظار چه اقدام عملی داشتید؟

نرگس محمدی – زندان اوین تهران

۱۹ مرداد ۱۴۰۳

در ادامه سوالات و جواب ها را میخوانید:

آگنس کالامار، دبیرکل سازمان عفو بینالملل

آگنس کالامارد میگوید: «ما روایتهای دردناکی از نحوه بازداشت زنان توسط دستگاههای اطلاعاتی و نیروهای امنیتی جمعآوری کردهایم. این زنان ساعتها تحت شکنجه قرار گرفته اند و انواع بد رفتاری ها، از جمله تجاوز و دیگر اشکال خشونت جنسی و روانی را تحمل کرده اند که تنها با هدف تحقیر و توهین انجام میشود. اگر آنها میتوانند زنده بمانند، سخن بگویند و مقاومت کنند، من چطور میتوانم جرات نداشته باشم؟ هرگز نمیتوانم خودم را بابت کوتاهی در خدمت به عدالت و دیگران ببخشم.»

– نرگس محمدی : جامعه بینالمللی چگونه میتواند بهطور مؤثرتری به مسئله آپارتاید جنسیتی رسیدگی کند، بهویژه در کشورهایی مانند ایران که زنان با سرکوبی بینهایت شدید مواجه هستند، اما واکنش جهانی در برابر آن ناکافی به نظر میرسد؟ چگونه میتوان این شکاف را برطرف کرد؟

– آگنس کالامار : نسلهای پیدرپی از زنان و دختران در سراسر جهان با خشونت و سرکوب سیستماتیک مواجه بودهاند. هزاران زن کشته شدهاند و بسیاری از زنان و دختران از کرامت، آزادی و برابری در زندگی روزمره خود محروماند. در ژوئن گذشته، سازمان عفو بینالملل به همراه فعالان برجستهای از ایران، افغانستان و دیگر نقاط جهان، از جامعه بینالمللی درخواست کرد که آپارتاید جنسیتی را بهعنوان یک جرم تحت قوانین بینالمللی به رسمیت بشناسد. این اقدام، یک خلاء بزرگ در چارچوب قوانین جهانی ما را پوشش میدهد و عنوانی برای این شکل وحشتناک تبعیض و سرکوب ارائه میدهد، و به فعالان حقوق بشر، صرفنظر از محل فعالیتشان، ابزاری حیاتی میدهد. دولتها باید به این درخواست توجه کنند. این نوع سرکوب باید نامگذاری شود و امکان تحقیق و پیگرد عاملان آپارتاید جنسیتی فراهم شود؛ به همان شکل که باید امکان تحریم کسانی که در این جنایات نقش دارند، وجود داشته باشد.

پیشنویس کنوانسیون جرایم علیه بشریت که اکنون در سازمان ملل متحد در حال بررسی است، فرصتی حیاتی برای تقویت مبارزه برای عدالت جنسیتی فراهم میکند. جامعه بینالمللی باید این فرصت را غنیمت شمارد و آپارتاید جنسیتی را به قوانین بینالمللی اضافه کند. در عین حال، دولتها باید از تمامی ابزارهای موجود، چه قانونی و چه دیپلماتیک، برای مقابله با این جنایات استفاده کنند.

اگرچه آپارتاید جنسیتی هنوز بهطور رسمی به رسمیت شناخته نشده است، اما جنایاتی که در این قالب رخ میدهند را میتوان معادل جنایت علیه بشریت دانست. دولتها باید در کشور خود تحقیقاتی کیفری علیه متهمان احتمالی آغاز کنند و بر اساس اصل صلاحیت جهانی، احکام بازداشت بینالمللی را صادر نمایند. همچنین باید از تمدید مأموریت کمیته حقیقتیاب سازمان ملل در ایران حمایت کنند تا این مکانیزم مستقل همچنان به جمعآوری، حفظ و تحلیل شواهد جنایات علیه زنان و دختران طبق قوانین بینالمللی ادامه دهد.

شورای امنیت سازمان ملل باید به درخواستها برای پاسخگویی به دولتها و افرادی که مسئول این نقضهای گسترده علیه زنان و دختران هستند، توجه کند. سازمانها و فعالان بینالمللی و ملی باید بیوقفه علیه بیتفاوتی که اغلب در واکنشهای رسمی به سرکوب زنان و دختران دیده میشود، مبارزه کنند.

– نرگس محمدی : اگنس، به عنوان شاهد خشونت سیستماتیک و آزار و اذیت زنان، چگونه با تأثیرات عاطفی و روانی داستانهایی که با شما به اشتراک میگذارند، کنار میآیید؟ چه چیزی شما را با وجود گزارشهای وحشتناک خشونتهایی که به شما ارائه میشود، به ادامه مبارزه برای عدالت ترغیب میکند؟

– آگنس كالامار : مشاهده تجاوزها و خشونتی که زنان و دختران در سیستمهای سرکوبگرانه تجربه میکنند، به شدت دردناک است. در ایران، سازمان عفو بینالملل شواهدی از استفاده از تجاوز جنسی و دیگر انواع خشونت جنسی برای سرکوب جنبش “زن، زندگی، آزادی” جمعآوری کرده است. ما گزارشهای تکاندهندهای از نحوه دستگیری خودسرانه زنان توسط نیروهای امنیتی، اعم از لباس شخصی و یونیفورمپوش، در خیابانها، خانهها یا محل کار آنها، در حین یا پس از اعتراضات دریافت کردهایم. بسیاری از این زنان ساعتها تحت شکنجه و آزارهای دیگر، از جمله تجاوز یا خشونت جنسی قرار میگیرند که هدف اصلی آن، تحقیر بیشترین حد ممکن است.

– این رویدادها همواره ما را به یاد قربانیان، بازماندگان و فعالانی میاندازد که برای جلوگیری از تکرار چنین فجایعی مبارزه میکنند و همچنین وظیفه اخلاقی ما برای کمک به آنها در رسیدن به عدالت را تقویت میکند. اگر آنها میتوانند زنده بمانند، سخن بگویند و مقاومت کنند، چرا من نتوانم؟ من هرگز نمیتوانم خودم را بابت کوتاهی در خدمت به عدالت و کمک به دیگران ببخشم. گواهی دادن بر این ظلمها تنها راه و اقدام مسئولانه است.

– رویکرد من شامل درک هم جنبههای شخصی و هم سیستماتیک این خشونتها است. ما باید این وقایع را در چارچوب قانونی و قضایی قرار دهیم و فرصتهایی برای اقدام و جبران خسارت شناسایی کنیم. آنچه بیش از هر چیز به من انگیزه میدهد، باور به این است که تغییر و عدالت ممکن است. وقتی من کارم را در زمینه حقوق زنان آغاز کردم، متقاعد کردن دولتها و همکاران حقوق بشری برای به رسمیت شناختن تجاوز به عنوان نوعی شکنجه بسیار دشوار بود. اما امروز این مسئله بهطور گسترده پذیرفته شده است، گرچه برای رسیدن به این شناخت مجبور به مبارزهای سخت بودیم. اکنون، بار دیگر باید بجنگیم، اینبار برای به رسمیت شناختن آپارتاید جنسیتی.

پینار سلیک، جامعهشناس، نویسنده و فعال ترکی، بنیانگذار انجمن آمارجی

«تو، من و خواهرانمان در سراسر جهان خوشبخت هستیم. آنها هرگز نمیتوانند ما را ناامید کنند. این خوشبختی ناشی از عشق، به ما زندگی و نشاط میبخشد. این احساس با تجربه همبستگی و خواهرانگی به اوج خود میرسد. دانستن اینکه من نقطهای کوچک در حرکتی بزرگ هستم به من کمک میکند تا مقاومت کنم. به این ترتیب، بار سرکوب را به تنهایی به دوش نمیکشم.» پینار سلیک

– نرگس محمدی : در کار شما درباره انسانهای به حاشیه رانده شده، به نظر میرسد مفهوم حاشیه نشینی اغلب بر گروه های خاصی تمرکز دارد. آیا معتقدید زنان هم به عنوان یک گروه حاشیه نشین در نظر گرفته میشوند؟ پویایی زنان چگونه با سایر گروههایی که شما مطالعه میکنید مقایسه میشود؟

– پینار سلیک : شما به درستی از افراد “به حاشیه راندهشده” صحبت میکنید، نه از “بیگانگان”، که این تفاوت بسیار مهم است. در غیر این صورت، ممکن است درباره افرادی عجیب، ضد اجتماعی، غیرعادی یا حتی هیولاوار صحبت کنیم. اما همانطور که بهخوبی بیان کردید، حاشیهنشینی به ویژگی ذاتی قربانیان اشاره نمیکند؛ بلکه این یک عمل ستمگرانه است. حاشیهنشینی نقشی نیست که قربانیان بهطور خودخواسته بپذیرند، بلکه تأثیرات قدرت است که در اشکال و درجات مختلف بروز میکند.

– تمدن بشری توسط تعاملات قدرت شکل گرفته و همواره مبارزهای بین تسلیم و رهایی در جریان است. برای اینکه مقاومت را غیرممکن یا ناکارآمد کنند، کسانی که در قدرت هستند، مکانیسمهایی را به کار میگیرند تا افراد را تضعیف، فقیر و نامرئی کنند. حاشیهنشینی نتیجه مستقیم این فرآیند است. به همین دلیل، من هرگز به معنای دقیق کلمه، بر روی “گروههای حاشیهنشین” کار نکردهام، بلکه تمرکزم بر روی مکانیسمها و استراتژیهای قدرت بوده است؛ مثلاً، پیوندهای بین ساختار اجتماعی بدنهای مردانه و تولید قدرت مردانه و خشونت سیاسی. من همچنین به کنشهای جمعی پرداختهام، یعنی مبارزات اجتماعی که در آنها شرکت داشتهام.

– از تجربه کار و مبارزاتم یاد گرفتهام که فرآیند حاشیهنشینی غیرقابل بازگشت نیست. از یک طرف، ستمگران تلاش میکنند تا قربانیان خود را بیقدرت، بیصدا و بیتأثیر کنند. اما از طرف دیگر، مظلومان منابع خود را برای مقابله با این استراتژیها بسیج میکنند. ما، بهعنوان زنان، قرنهاست که با قدرتهای مردسالارانهای که از دیگر نیروهای قدرت تغذیه میکنند، مبارزه کردهایم. با وجود این مبارزه طولانی، هنوز نتوانستهایم نظم اجتماعی را بهطور کامل دگرگون کنیم. برعکس، این نظم با جهانیسازی اقتصاد نئولیبرال و تقویت محافظهکاریها و فاشیسمها، بیش از پیش مستحکم شده است. شکافهای اجتماعی در سطح جهانی، گروههای آسیبپذیر را بیش از گذشته در معرض خطر قرار داده است.

– با این حال، مبارزات ما نیز قویتر شدهاند. برای مثال، در مورد تو، نرگس، آنها تمام تلاش خود را میکنند تا تو را به حاشیه برانند و از بین ببرند. اما تو، حتی در حالی که زندانی و سرکوب شدهای، همچنان غیرقابلمهار باقی ماندهای.

– نرگس محمدی: با وجود آزارها و دشمنیهایی که از سوی کشورتان تجربه میکنید، چطور همچنان به آرمانهای خود ایمان دارید و برای عدالت مبارزه میکنید؟ چه منابع درونی یا حمایتهای بیرونی به شما کمک میکنند تا در این مسیر پرفراز و نشیب ادامه دهید؟

– پینار سلیک : فکر میکنم، مثل تو، من هم برای پیدا کردن نیروی بیشتر، منابع مختلفی را به کار میگیرم و این کار را همیشه انجام میدهم! بزرگترین منبع من عشق است؛ توانایی عشقورزیدن و ادامه دادن آن. وقتی با فکر کردن به کسی به او احترام و لذت میبخشی، هرگز ناراحت نخواهی بود. ما، تو و دوستانمان، زنانی شاد هستیم. هیچوقت نمیتوانند ما را ناراحت کنند. این شادی که از عشق سرچشمه میگیرد، به ما نیروی زندگی میدهد و در تجربه همبستگی به اوج خود میرسد. دانستن اینکه من بخشی کوچک از یک تصویر بزرگتر هستم، به من کمک میکند مقاومت کنم. این حس باعث میشود که فشار ستمها را بهتنهایی احساس نکنم. همچنین به من حس مسئولیت میدهد. به خودم میگویم: «میان ما، این نقاط کوچک، ارتباطاتی وجود دارد و اگر من سقوط کنم، دیگری هم تعادلش را از دست میدهد…» تحلیلهای فلسفی و سیاسی دور من مانند کرمهای شبتاب میچرخند. به گفته معروف گرامشی فکر میکنم: «باید بدبینی عقل را با خوشبینی اراده ترکیب کنیم.» من شادی را در مبارزه با بیرحمیها پیدا میکنم. بدبینی را میپذیرم و این مرا قویتر میکند. الان از دوران نوجوانیام قویتر هستم. فهمیدهام که تغییر دنیا در دو روز ممکن نیست. دیگر شکستها، اشتباهات و شروعهای دوباره مرا از پا نمیاندازند. نمینشینم و تعجب نمیکنم که چرا بعضی چیزها تغییر نمیکنند. سهم خودم از عشق و آغوشها را دریافت میکنم. به بل هوکس فکر میکنم که میگفت وقتی نظریههای فمینیستی با گفتوگوهای تازه با دیگر منتقدان اجتماعی دوباره زنده میشوند، میتوانند مثل یک عصای جادویی دنیا را تغییر دهند. مبارزات فمینیستی امروز گستره وسیعی از امکانات را بررسی میکنند و با همگراییهای جدید در بسیجهای چندوجهی همراهاند. تعامل فمینیسمهای مختلف، فضاها و تجربیات گوناگون به گسترش گروهها، استراتژیها، اتحادها و بحثهای بیشتری منجر میشود. حالا ما ابزارهای بیشتری، تجربیات بیشتری و مسیرهای بیشتری برای تأمل و مبارزه در اختیار داریم.

– نرگس محمدی : مفهوم خواهرانگی برای شما چه معنایی دارد و چه زمانی اولین بار این حس همبستگی زنانه را تجربه کردید؟ خواهرانگی چگونه بر کار و تعهد شما برای حقوق زنان تأثیر گذاشته و کمک کرده است؟

– پینار سلیک : اولین تجربه من از حس خواهرانگی با خواهر کوچکم، سیدا، بود. از او یاد گرفتم عشق خواهرانه چیست و چطور آن را پرورش دهم. همین تجربه به من کمک کرد که وارد دنیای خواهرانگی بدون مرز شوم. ما در شرایط سختی بزرگ شدیم. همیشه تلاش میکردیم حس کنیم بخشی از یک داستان هستیم، اما نویسنده آن داستان انگار مدام ما را امتحان میکرد. شب کودتای نظامی ۱۹۸۰ یادم هست. سربازان به خانه ما آمدند، پدرمان زندانی شد و مادرم بیمار. بیمارستان، زندان، مدرسه، اشکها و درگیریها بخشی از زندگی ما بود. ما خیلی کوچک بودیم، اما دست در دست هم مقاومت کردیم. بارها از دل آتش فرار کردیم و همدیگر را نجات دادیم، نه یک بار، نه صد بار. دوران سختی داشتیم، ولی با هم دوام آوردیم و به هم امید دادیم.

– با بزرگ شدن، تفاوتهایمان بیشتر مشخص شد. هر کدام راه خودمان را رفتیم. فهمیدیم که شبیه بودن همیشه مهم نیست، اگر یکی باغ را دوست داشته باشد و دیگری زمین ذرت را. وقتی من زندانی شدم، سیدا کارش را رها کرد تا حقوق بخواند و وکیل من شود. او موفق شد و حالا بیش از ۲۶ سال است که چشمها، دستها و پاهای پرونده من است. او بار دادگاههای من را به دوش میکشد و بیشتر از من فکر میکند که چه باید کرد و چه نباید کرد. از او یاد گرفتم که عشق و پیوند خواهرانه وابسته به شباهت نیست، بلکه از تفاوتها و اشتراکات رشد میکند.

– این تجربه به من کمک کرد که به خواهران دیگری هم باز شوم. آسان نبود، دشوار بود، خیلی دشوار. چون تمرکز بر فردی دیگر که شاید تجربههای کمتری داشته یا از زمینه اجتماعی و سیاسی متفاوتی آمده، نیاز به تلاش بیشتری داشت. سیدا و من از یک خانواده و شرایط مشابه میآییم، اما ایجاد ارتباط قوی با زنانی که با مشکلات دیگری روبرو هستند، نیاز به تفکر، گوش دادن، پرسش و بازنگری بیشتری داشت. این یک تلاش مداوم است. حالا میبینم که درهای زیادی برای خواهرانگی وجود دارد و هر کدام را که باز کنید، درهای بعدی را راحتتر باز خواهید کرد. من این را دوست دارم و از آن لذت میبرم.

تاتیانا موکانیری بندالییر، فعال کنگویی، هماهنگکننده ملی جنبش ملی بازماندگان خشونت جنسی در جمهوری دموکراتیک کنگو و نویسندهی کتاب «فراتر از اشکهای ما»

«روایتگری آزادیبخش است؛ حرف زدن از رنج به قربانی کمک میکند تا بر شرم خود غلبه کند، با کسانی که به او برچسب میزنند، روبرو شود، آنچه که رخ داده است را افشا کند و از همه مهمتر، به متجاوز نشان دهد که سکوت بالاخره خواهد شکست. روایت گری میتواند به زنان قدرت دهد و انگیزهای برای سایر قربانیان باشد تا بدانند که بهبودی ممکن است، و میتوان از گذشتهی تراژیک به آینده با خوشبینی نگاه کرد.» تاتیانا موکانیری بندالییر

– نرگس محمدی : در کتاب تحسین برانگیز «فراتر از اشکهایمان»، با شجاعت بینظیر به شکنجه و تجاوزی که متحمل شدهاید پرداختهاید. آیا باور دارید که به اشتراک گذاشتن تجربیات تجاوز، شکنجه و آزار جنسی میتواند به زنان قدرت ببخشد؟ چقدر مهم است که زنان به طور آشکار در مورد این تجربیات صحبت کنند، هم برای درمان و هم برای محافظت از دیگر زنان آسیب دیده؟

– تاتیانا موکانیری بندالییر: من عمیقاً معتقدم که به اشتراک گذاشتن تجربیات مربوط به تجاوز، شکنجه و آزار جنسی میتواند به زنان قدرت بدهد، چون این کار به دردهای ما کلمات میبخشد و زخمهای ما را آشکار میکند. صحبت کردن درباره آنچه بر ما گذشته است، نوعی خوددرمانی است. حرف زدن به ما کمک میکند سکوت خود را بشکنیم و باری را که به عنوان قربانی بر دوش داریم سبک کنیم، مخصوصاً وقتی که این رنجها را در تنهایی و ناشناسی تحمل کردهایم و جامعه به جای محکوم کردن مجرم، قربانی را سرزنش میکند. خیلی وقتها میشنویم که میگویند قربانی به خاطر نوع لباسش مورد تجاوز قرار گرفته است و خودش مقصر است.

– توانایی صحبت کردن درباره این دردها بسیار رهاییبخش است، چون به قربانی کمک میکند بر حس شرم غلبه کند، با کسانی که او را سرزنش میکنند روبرو شود، آنچه اتفاق افتاده است را محکوم کند و مهمتر از همه به مجرم نشان دهد که سکوتش دیر یا زود شکسته خواهد شد. به اشتراک گذاشتن این تجربیات، به زنان قدرت میدهد و الهامبخش زنانی است که در سکوت زندگی کردهاند. این کار به دیگر قربانیان نشان میدهد که بهبودی و رهایی از این رنجها امکانپذیر است و میتوان از گذشتهای تراژیک عبور کرد و به آیندهای امیدوار نگاه کرد.

– این دقیقاً مأموریت جنبش ملی بازماندگان خشونت جنسی در جمهوری دموکراتیک کنگو است که ما راهاندازی کردیم. از طریق یک مدل حمایتی، ما بازماندگان را تشویق میکنیم که به یکدیگر کمک کنند و با شکستن سکوتشان، به جلو حرکت کنند. آنها میفهمند که تنها نیستند و کسانی که تجربیات مشابهی دارند، میتوانند از یک قربانی به یک رهبر و عامل تغییر در جامعه خود تبدیل شوند.

– نرگس محمدی : در کشور من، ایران، زنان به دلیل رقصیدن، آواز خواندن یا نپوشیدن حجاب اجباری مطابق با خواستههای دولت دستگیر، زندانی و کشته میشوند. فرهنگ کشور من و تو از نظر موسیقی، رقص و آواز برای زنان چه تفاوت هایی دارد؟ و این موضوع از بعد آپارتاید جنسیتی چه معنایی برای شما دارد؟

– تاتیانا موکانیری بندالییر: در ایران و بسیاری از کشورهای دیگر، زنان با موانعی روبرو میشوند که هنجارهای اجتماعی برای آنها ایجاد میکند و جلوی پیشرفتشان را میگیرد. در برخی کشورها، زنان ناچارند اعمالی مثل ختنه یا ازدواج در کودکی را تحمل کنند. از نظر هنری، مانند موسیقی و رقص، فرهنگها متفاوتاند. در کنگو، زنان میتوانند آزادانه بدون ترس از دستگیری یا به خطر انداختن جانشان آواز بخوانند، برقصند و موسیقی بنوازند. یکی از دلایل این آزادی این است که جمهوری دموکراتیک کنگو کشوری سکولار است و هیچ قانون مذهبی زنان را به انجام رفتار خاصی مجبور نمیکند.

– علاوه بر این، قانون اساسی کنگو از زنان محافظت میکند. برای مثال، ماده ۱۴ قانون اساسی برابری جنسیتی را تضمین کرده است. این قوانین مانع از آن میشود که زنان کنگویی به خاطر آواز یا رقص خود دستگیر یا مجازات شوند. با این وجود، اجرای این قوانین در مناطق مختلف کشور همچنان چالشبرانگیز است، جایی که زنان با انواع سوءاستفادهها و خشونتها روبرو هستند.

– این مشکلات اغلب توسط آداب و رسومی تشدید میشود که محدودیتهای اجتماعی سختی را به زنان تحمیل میکنند. خشونت جنسی، ازدواج اجباری کودکان و خشونت خانگی هنوز هم در جمهوری دموکراتیک کنگو رخ میدهد. همچنین باورهای اجتماعی که زنان را از نظر فکری پایینتر از مردان میدانند، مانع پیشرفت زنان شده و دسترسی آنها به تحصیلات، شغل و جایگاههای رهبری را محدود میکند.

– در زمان جنگ و درگیریهای مسلحانه، از خشونت جنسی به عنوان سلاح جنگی استفاده میشود و زنان کنگویی بیشتر قربانی این درگیریها هستند. خشونت جنسی که صدها هزار زن را تحت تأثیر قرار داده، تأثیرات جدی بر سلامت جسمی و روانی آنها داشته و موجب انزوای اجتماعی و انگ زدن به آنها شده است.

– با این حال، در جمهوری دموکراتیک کنگو نمیتوان به راحتی از «آپارتاید جنسیتی» صحبت کرد زیرا خشونت علیه زنان به صورت سیستماتیک و دولتی نهادینه نشده است. اگرچه زنان با چالشها و خشونتهای زیادی روبرو هستند، هیچ سیاست دولتی مشخصی برای تبعیض علیه زنان وجود ندارد. با این حال، ضروری است که تلاش کنیم تا قوانین محافظت از زنان به درستی اجرا شوند و سنتهای مخرب که جلوی پیشرفت آنها را میگیرد، از بین برود.

الکساندرا ماتویچوک، وکیل و فعال اوکراینی، رهبر سازمان غیردولتی مرکز آزادیهای مدنی، برنده جایزه صلح نوبل در سال ۲۰۲۲

«مبارزهی شما مبارزهی ماست. تجربهی من به من آموخته است که وقتی فرآیندهای قانونی شکست میخورند، همیشه میتوانیم به مردم تکیه کنیم. مردم عادی قدرت بیشتری از آنچه که تصور میکنند، دارند. آیندهی ما نامشخص است، اما توسط هیچکس از پیش تعیین نشده است. به همین دلیل است که ما فرصت داریم برای آیندهای که برای خود و فرزندانمان میخواهیم، بجنگیم.» الکساندرا ماتویچوک

- نرگس محمدی: به عنوان یک مدافع حقوق بشر که در اوکراین و کشورهای سازمان امنیت و همکاری اروپا (OSCE) فعالیت میکنید، چگونه خشونت جنسیتی با کارهای شما در زمینه مستندسازی نقض حقوق بشر پیوند میخورد؟ چه رویکردها یا استراتژیهایی را در پرداختن به مسائل جنسیتی مؤثرتر میدانید؟

– الکساندرا ماتویچوک : در ده سال گذشته، ما جنایات جنگی، از جمله خشونت جنسی، که در جریان درگیری آغاز شده توسط روسیه رخ داده است را مستند کردهایم و بسیاری از بازماندگان این خشونتها زنان هستند. این نوع خشونت ادامهای از جنگ است که بدن زنان را به عنوان سلاح مورد استفاده قرار میدهد. سربازان روسی با هدف قرار دادن جوامع اشغالشده، به این روند ادامه میدهند. بازماندگان این خشونت احساس شرم میکنند، خانوادههای آنها به خاطر این وقایع احساس گناه میکنند وجامعه به طور کلی با ترس روبرو میشود. این مجموعه پیچیده از احساسات باعث تضعیف پیوندهای اجتماعی شده وبه ارتش روسیه اجازه میدهد کنترل بیشتری بر مناطق اشغالی داشته باشد.

– اما نمیخواهم این تصور غلط را به وجود بیاورم که زنان در زمان جنگ تنها قربانی هستند. تجربه ما نشان میدهد که زنان در خط مقدم مبارزه برای آزادی وکرامت انسانی قرار دارند. آنها در نیروهای مسلح خدمت میکنند، در تصمیمگیریهای سیاسی نقش دارند، جنایات جنگی را مستند میکنند وابتكارات اجتماعی را رهبری میکنند. شجاعت هیچ جنسیتی را نمیشناسد. به نظر من، یکی از بهترین استراتژیها برای تحقق برابری جنسیتی این است که زنان از یکدیگر حمایت کنند.

– نرگس محمدی: چگونه جنبشهای فمینیستی جهانی میتوانند بهتر صدای زنان و گروههای به حاشیه رانده شده که مستقیماً تحت تأثیر درگیریها و رژیم های اقتدار گرا هستند را یکپارچه و تقویت کنند؟

– الکساندرا ماتویچوک : ما باید به نقض حقوق زنان در سایر کشورها پاسخ دهیم. دنیای ما بسیار به هم پیوسته است و مبارزه زنان در ایران بر آینده ما تأثیر میگذارد. رژیم های اقتدار گرا همیشه صداهای زنان را سرکوب میکنند و تلاش میکنند تصمیمات آنها را کنترل کنند. در نتیجه، نقشهای محدود و دقیقی به زنان در خانواده و جامعه اختصاص داده میشود. این یک پایه اصلی اقتدار گرایی است، زیرا نحوه رفتار با افراد نشاندهنده چگونگی رفتار قدرت با شهروندانش است. به همین دلیل است که در نروژ زنان و مردان حقوق یکسان دارند، در افغانستان زنان از ورود به دانشگاهها منع میشوند و در روسیه خشونت خانگی جرم زدایی شده است. شخصی به سیاسی تبدیل میشود زیرا همیشه با نحوه رفتار قدرت با مردم مرتبط است. بنابراین، وقتی ما برای حقوق زنان مبارزه میکنیم، برای آینده دختران مان مبارزه میکنیم. ما نمیخواهیم آنها مجبور باشند به کسی ثابت کنند که آنها نیز انسان هستند.

– نرگس محمدی: چگونه میتوانیم اقدام بین المللی مؤثر و همبستگی را برای پایان دادن به آپارتاید جنسیتی در سراسر جهان برقرار کنیم؟ و چه توصیه ای به زنان ایرانی میکنید تا در مبارزه شان برای حقوق زنان از آن استفاده کنند؟

– الکساندرا ماتویچوک : مبارزه شما، مبارزه ماست. در اوکراین، ما نیز در موقعیتی قرار داریم که قانون بیاثر است و سازمان ملل نمیتواند از وقوع جنایات روسیه جلوگیری کند. اما تجربه شخصی من به من آموخته است که وقتی فرآیندهای قانونی شکست میخورند، ما همیشه میتوانیم به مردم تکیه کنیم. مردم عادی قدرت بیشتری نسبت به آنچه تصور میکنند دارند. آینده ما نامشخص است، اما توسط هیچکس از پیش تعیین نشده است. به همین دلیل، ما فرصت مبارزه برای آیندهای را داریم که برای خود و فرزندانمان میخواهیم.

شیرین عبادی، فعال سیاسی ایرانی، وکیل، قاضی سابق و مدافع حقوق بشر، برنده جایزه صلح نوبل در سال ۲۰۰۳

«از زنان در سراسر جهان میخواهم که از کسانی که از آموزش محروم هستند، چه به دلیل دلایل سیاسی مانند زنان افغانستان چه به دلایل دیگر مثل فقر حمایت کنند. هر چه زنان و دختران توانمندتر باشند، در مبارزه با تبعیض قویتر خواهند بود.» شیرین عبادی

– نرگس محمدی : به عنوان اولین زن قاضی، چالشهای اصلی شما در شکستن موانع سیستم قضایی مردسالار چه بود؟ چگونه بر دیدگاه نسبت به زنان در سیستم قضایی ایران تأثیر گذاشتید؟

– شیرین عبادی : من در اسفند ۱۳۴۸ قاضی شدم و در آن زمان زن بودن من برای دولت مشکلی ایجاد نمیکرد. من بدون هیچ مانعی و مانند همتایان مرد خود، آزمونها را گذراندم و موفق شدم و به مقام قضاوت رسیدم. شاه میخواست ایران را به تمدن غربی نزدیک کند، بنابراین خودش ابتکار اعطای بسیاری از حقوق به زنان، از جمله حق قضاوت، حق حضانت و حق طلاق را آغاز کرد. به همین دلیل دولت با آن مخالفتی نداشت و من نیز مانند سایر زنان از حمایت دولت برخوردار بودم. همچنین باید بگویم که از طرف جامعه نیز با مشکلی روبرو نشدم. به یاد نمیآورم که در زمان قضاوت با مسائلی خاص به دلیل زن بودن مواجه شده باشم.

– نرگس محمدی : وقتی دولت ایران زنان را از دستگاه قضایی حذف کرد، این تصمیم چه تأثیری بر زندگی حرفهای شما و کارتان به جهت برابری جنسیتی داشت؟ پیامدهای فوری و بلند مدت این سیاست برای حقوق زنان در ایران چه بود؟

– شیرین عبادی: بعد از انقلاب اسلامی، یکی از اولین تصمیمات این بود که زنان دیگر نمیتوانند قاضی باشند. من و سایر زنان قاضی به مشاغل اداری منتقل شدیم. این اتفاق بسیار ناامیدکننده بود زیرا زنان بخش مهمی از قدرت خود را از دست دادند. با این حال، این موضوع مانع از ادامه تحصیل دختران جوان در رشته حقوق نشد. زمانی که من دانشجو بودم، در کلاس ما ۲۰۰ نفر حضور داشتند که تنها ۳۰ نفرشان زن بودند. اما چند سال بعد، وقتی دخترم فارغالتحصیل شد، در جمهوری اسلامی ایران تعداد زنان دانشجوی حقوق دو برابر مردان بود. علیرغم شرایط تبعیضآمیز، زنان نیاز به دانش حقوقی را حس کردند و این امر علاقه آنها را به تحصیل در این رشته افزایش داد.

– نرگس محمدی؟ به عنوان اولین زن ایرانی که جایزه صلح نوبل را دریافت کردید، چه چالشها و فرصتهایی را هم در ایران و هم در عرصه بینالمللی تجربه کردید؟ این دستاورد چگونه بر تلاشهای بعدی شما در زمینه حقوق بشر و برابری جنسیتی تأثیر گذاشت؟

– شیرین عبادی: من پول جایزه نوبل را صرف خرید یک دفتر در ایران کردم تا یک سازمان غیردولتی تأسیس کنم که همبنیانگذار و رئیس آن هستم. این دفتر به مرکزی تبدیل شد که بسیاری از وکلای جوان، از جمله شما، نرگس، را به خود جذب کرد. ما خدمات رایگان به زندانیان سیاسی ارائه میدادیم و هر ماه گزارشهایی از نقض حقوق بشر در ایران به سازمان ملل ارسال میکردیم. ما جزو اولین کسانی بودیم که این کار را شروع کردیم و خوشبختانه از آن زمان دیگران هم این مسیر را ادامه دادند. امروزه وکلای زیادی به صورت رایگان به متهمان سیاسی خدمات ارائه میدهند و درباره این پروندهها گزارش میکنند.

– نرگس محمدی : چه پیامی برای زنان در سراسر جهان که در تلاش برای غلبه بر موانع سیستماتیک و پیشبرد برابری جنسیتی هستند، دارید؟ آنها چگونه میتوانند از تجربیات فردی و جمعی خود برای ایجاد تغییرات مثبت در جوامع خود و فراتر از آن استفاده کنند؟

– شیرین عبادی: زنان در سراسر جهان باید درک کنند که ریشه اصلی تبعیضی که با آن روبرو هستند، فرهنگ مردسالار است. این فرهنگ برای توجیه خود از هر چیزی استفاده میکند. بهعنوان مثال، وقتی مذهب قدرت میگیرد، از آن بهعنوان بهانهای برای سرکوب استفاده میکند. در ایران و افغانستان، سرکوب و تبعیض اغلب به نام اسلام توجیه میشود، در حالی که علت واقعی آن، فرهنگ مردسالار است. در برخی کشورها، مشکل تنها قوانین نیست، بلکه سنتهای اجتماعی هستند که با زنان مخالفاند. بنابراین، مهمترین وظیفه زنان شناسایی منبع تبعیض است. اولین قدم، افزایش آگاهی و آموزش زنان است. ما میدانیم که چرا طالبان زنان را از تحصیل منع کردهاند؛ زیرا آنها میدانند که یک زن تحصیلکرده حتماً با آنها مخالفت خواهد کرد. من از زنان در سراسر جهان میخواهم از کسانی که به دلایل سیاسی، مانند زنان افغان، یا به دلیل فقر و سایر عوامل، از آموزش محروم شدهاند، حمایت کنند. هر چه این زنان توانمندتر شوند، در مبارزه با تبعیض قویتر خواهند بود.

آن لویییه، فیزیکدان فرانسوی-سوئدی، برنده جایزه نوبل در فیزیک در سال ۲۰۲۳

«زنان باید به همان اندازه که مردان به آموزش دسترسی دارند، دسترسی داشته باشند. این یک حق بنیادی است که ملیتها، قومیتها یا ادیان را دربرمیگیرد. آنها باید به آموزش عالی و سپس به مشاغل صنعتی یا علمی به همان شیوهای که مردان دارند، دسترسی پیدا کنند.» آن لویییه

– نرگس محمدی : چرا علوم هنوز به نظر میرسد که بهطور عمده یک حوزهای است که برای مردان محفوظ است و چه اقداماتی میتوان برای تغییر این وضعیت انجام داد؟

– آن لویییه : زنان باید به همان اندازه که مردان به آموزش دسترسی دارند، دسترسی داشته باشند. این یک حق اساسی است که از مرزهای ملیت، قومیت یا دین فراتر میرود. آنها باید به آموزش عالی و سپس به مشاغل صنعتی یا دانشگاهی دسترسی داشته باشند، به همان شیوهای که مردان دارند. این امر برای پیشرفت علم و فناوری که برای حل مشکلات بشریت و بهبود شرایط زندگی ما حیاتی است، بسیار مهم است. زنان جوان در صورتی که حمایت جامعه، والدین، معلمان و غیره را احساس کنند، به سمت مشاغل علمی و فنی خواهند رفت. تجربه من این است که یک تیم زمانی بسیار کارآمدتر و مؤثرتر است که متنوع باشد. به عبارت دیگر، جذب زنان به این مشاغل یک مسئله مهم برای بشریت است.

دکتر جین گودال، اتولوژیست و انسانشناس بریتانیایی، بنیانگذار مؤسسه جین گودال

«ما پول زیادی نداشتیم و من فقط یک دختر بودم. مادرم به من گفت که باید بسیار سخت کار کنم، از همه فرصتها استفاده کنم و هرگز تسلیم نشوم. این پیام را با جهان، به ویژه با دختران و کسانی که از امکانات کمبرخوردار هستند، به اشتراک گذاشتهام و آنها را تشویق کردهام که همیشه به رویاهایشان ایمان داشته باشند.» دکتر جین گودال

– نرگس محمدی : میتوانید موانعی را که به عنوان یک زن جوان در حال انجام تحقیقات پیشگامانه روی نخستیها در تانزانیا با آن مواجه شدید، و چگونگی غلبه بر آنها را بازگو کنید؟ حضور و کار شما در رشتهای عمدتاً مردانه چگونه بر جامعه علمی و درک محلی از نقشهای جنسیتی تأثیر گذاشت؟

وقتی دکتر لوییس لیکی از من پرسید آیا میخواهم رفتار شامپانزههای وحشی را مطالعه کنم، من به دلیل محدودیتهای مالی نتوانسته بودم به دانشگاه بروم. بنابراین با علاقهام به تمام حیوانات، یک جفت دوربین، یک دفترچه یادداشت، یک مداد و میل شدیدی به یادگیری بیشتر درباره نزدیکترین خویشاوندانمان شروع کردم.

این رشته تحت سلطه مردان نبود، چون ناشناخته و جدید بود و در واقع، تنها سه مطالعه میدانی در طبیعت وجود داشت: گوریلها در رواندا، بابونها در آفریقای جنوبی و ماکاکهای ژاپنی در ژاپن. هرچند این تحقیقات توسط مردان هدایت میشد، اما این زمینه از مطالعات بهطور کلی جدید بود. زن بودن گاهی به من کمک کرد. آن زمان تانزانیا تازه استقلالش را از بریتانیا به دست آورده بود و مردان سفیدپوست چندان محبوب نبودند. اما به عنوان یک زن جوان، آفریقاییها تمایل بیشتری برای کمک به من داشتند.

وقتی لیکی به من خبر داد که جایی برای من در دانشگاه کمبریج برای دکتری اتولوژی پیدا کرده است، بسیاری از رسانهها ادعا کردند که من فقط به دلیل جذابیت ظاهریام، به ویژه پاهایم، این بودجه تحقیقاتی را دریافت کردهام. اما من فقط به خاطر خشنود کردن لیکی این مدرک را دنبال نمیکردم؛ بلکه میخواستم به کارم با شامپانزهها بازگردم و به حرفهای مردم اهمیتی ندادم.

موقعیت من بسیار متفاوت از چالشهایی است که زنان روزانه با آنها روبرو هستند.

– نرگس محمدی : چه استراتژیای را برای مبارزه با تبعیض سیستماتیک علیه زنان مؤثرتر میدانید؟

– دکتر جین گودال : من در سال ۱۹۳۴ در خانوادهای خارق العاده به دنیا آمدم. ما پول زیادی نداشتیم و این بین دو جنگ جهانی بود. مادربزرگم یکی از اولین زنانی بود که در انگلستان قبل از ازدواج شغل داشت و نوعی ژیمناستیک ملایم را در یک مدرسه دخترانه تدریس میکرد. دختر بزرگ ترش یکی از اولین زنانی بود که در انگلستان به عنوان فیزیوتراپیست در بیمارستان گایز کار میکرد. وقتی ۱۰ ساله بودم و تصمیم گرفتم وقتی بزرگ شدم، به آفریقا بروم، با حیوانات وحشی زندگی کنم و کتابهایی درباره آنها بنویسم، همه مرا مسخره کردند. چطور میتوانستم این کار را انجام دهم؟ ما پول زیادی نداشتیم، آفریقا دور بود و من فقط یک دختر بودم. مادرم فقط به من گفت که خیلی سخت کار کنم، از تمام فرصتها استفاده کنم و تسلیم نشوم. این پیامی است که من به همه جهان منتقل کردهام، به ویژه به دختران جوان و کسانی که از سرزمین های محروم هستند، و آنها را تشویق کردهام که همیشه به رویاهای خود باور داشته باشند.

– نرگس محمدی: شما از فعالان محیط زیست ایرانی که به خاطر فعالیتهایشان سالها زندانی بودند، حمایت کردید. چه چیزی باعث این حمایت شما شد؟ چه ارتباطی بین نابرابری جنسیتی وتخریب محیط زیست مشاهده میکنید؟ وزنان چگونه میتوانند در حل این بحرانهای پیچیده نقش مؤثری ایفا کنند؟

دکتر جین گودال : من بسیار ناراحت شدم که این جوانان مدافع محیط زیست، از جمله دو زن، به دلیل اتهامات دروغین جاسوسی زندانی شدند. این اتفاق به این خاطر بود که آنها از دوربینهای تلهای برای ضبط ویدئوهایی از یوزپلنگها، پلنگها و دیگر حیوانات خجالتی استفاده میکردند. من نامهای نوشتم واز دولت ایران خواستم تا فورا آنها را آزاد کند، اما این اقدام تأثیری نداشت. سپس به آنها در زندان نامه نوشتم تا حداقل بدانند فراموش نشدهاند. آنها به من گفتند که این نامهها برای روحیهشان مهم بوده، بنابراین من به نوشتن ادامه دادم و خوشبختانه،

همه آنها امروز آزاد هستند.

در مؤسسه جین گودال، ما کارهای زیادی برای بهبود تحصیل دختران در مناطق فقیر تانزانیا و سایر کشورهای آفریقایی انجام میدهیم. ما به زنان روستایی وامهای کوچک میدهیم تا کسبوکارهای سازگار با محیط زیست خود را راهاندازی کنند. در طول عمرم، تغییرات زیادی در نگاه نسبت به زنان مشاهده کردهام، اما این مسئله در کشورهایی مانند ایران، افغانستان و بسیاری از کشورهای دیگر متاسفانه صدق نمیکند. در برخی نقاط کره زمین زنان بیشتری به موقعیتهای بالای سیاسی دست یافتهاند و در عرصههای مختلف، از جمله به عنوان مدیرعامل و حتی در نیروهای مسلح، حضور دارند. همچنین زنان سازمانهای محافظت از جنگلهای بسیار خوبی نیز به وجود آورده اند. با این حال، واقعیت این است که در بسیاری از کشورها زنان همچنان با تبعیض زیاد بهویژه در زمینه دستمزد، مواجه هستند.